SURTITLED THEATRICALITY. WHAT LANGUAGE DO ARTISTS EXPORT?

If certain theatre artists decide to leave their country and start a career elsewhere, reshaping their style to the peculiarities of a foreign audience, others export their work as samples of the kind of theatre that these artists have learned to extract. So what is the essence of their artistic choices? And to what degree does it depend on the addressees’ environment?

Traveling Europe to see theatre—as the Young European Journalists on Performing Arts are doing in the context of the UTE “Conflict Zones” programme—always comes down to the question of “exportability”, especially regarding those performances presented in so-called “international events”.

It goes without saying that dance and music have the extraordinary ability to be really universal, because they are not based on fixed codes of language: the absence of the spoken word—or the challenge presented to its supremacy—brings the semiotics of performance to a more physical, empathic and immediate level.

The question is: how and why does an artist choose to export one show or another? Is he/she aware of the level of engagement that is needed in order for it to be fully received by a foreign audience?

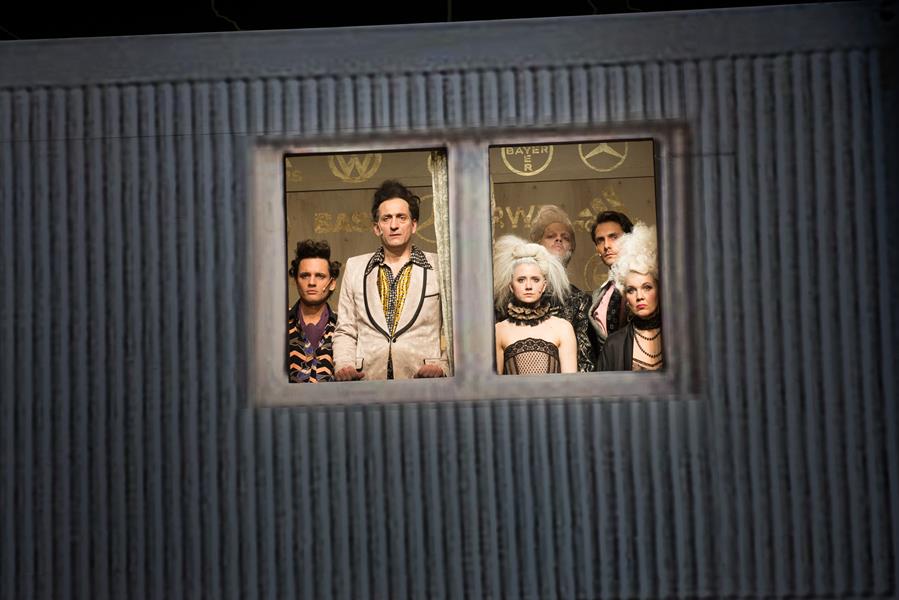

Sample #1. On the 1st of December, the Main Hall opened the curtain for the Ukrainian stage director Andriy Zholdak’s staging of Electra, produced by the National Theatre of Macedonia, a very dark adaptation of the Greek classic “based on Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides”. In the first act, a giant container, with windows and sliding doors, frames four different spaces: a studio/bedroom, a corridor, a bathroom, a kitchen. On the top of the structure, two lateral screens project live feed video of the actors’ close-ups and details of the scene. Thus, the spectators are invited to switch their attention from one side to the other, chasing a very complex montage of actions and emotions. Separated from the narrative—and yet crucial for the understanding—hanged to the ceiling there are two more screens that play the surtitles: English, Romanian and Hungarian on the centre, Macedonian on the side. Then the audience’s attention must be split in at least one more way, depending on the mother tongue of the spectator, who at the same time is listening to a text spoken in a foreign language. Fortunately, the general taste of the performance doesn’t lean much on words, but rather on impressive images and deeply emotional acting style, not without a generous touch of Grand-Guignol in the killing scenes.

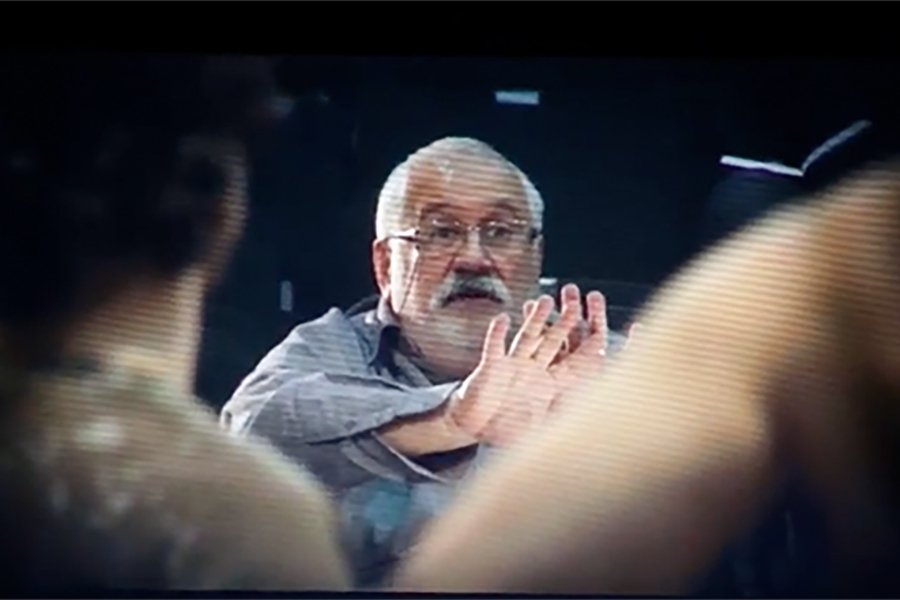

Sample #2. The next day, the same venue hosted Andrei Șerban’s staging of Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Person of Szechwan for the Bulandra Theatre, Romania. The actors, with faces painted in white, mingle up text and songs on a simple but colourful set, trying to recreate a “genuine” Brechtian imagery. In this case, the fact that the plot is quiet familiar to anybody interested in modern and contemporary theatre was of great help, since once again it wasn’t always easy to follow the surtitles (in Hungarian and English).

Sample #3. December the 2nd was also the night of the Sfumato Theatre Laboratory from Sofia, Bulgaria. OOOO – The Dream of Gogol is a very well crafted journey into Nikolai Gogol’s imagery, with excerpts from different short stories, carried out by a tight-knit group of performers. The mood is always halfway between humourous, ironic, dark and desperate; with only a platform and a backwall as a set, some hatches, well designed lights, simple props and an impressive acting talent fully entertaining the audience. The rhythm of the spoken word—frequently delivered by at least three performers simultaneously—is the key to organize such a rigorous physical theatre on stage. Once again, flooded by such a copious river of words in Bulgarian, the attention goes through some hard times in trying to follow the written text, which is streaming on the screen in very dense and quick bicoloured slides.

Sample # 4. December 3rd, back in the Main Hall. The festival hosts the great talent and South-Korean storyteller Jaram Lee (here directed by Ji Hye Park). Her pansori (this is the name of the traditional form of musical storytelling performed by a vocalist and a drummer) The Stranger’s Song needs nothing more than some space to move, a fan and two musicians (playing buk and guitar). In this adaptation of Gabiel Garcia Marquez’s novella Bon Voyage, Mr. President (published in 1993 in The New Yorker), the surtitles are still there, up on the screen doing their translating job into three languages. And yet, the whole performance is so much attached to body language and meticulously built on the relationship between performer and spectator, that one no longer needs to read the text word by word. Thanks to Lee’s clever attitude in putting the audience at ease, and certainly to a simple but powerful story, we manage to follow the path from pantomime to poetry, without worrying too much about the exact sentences.

Since these four samples cannot exhaustively give an account of all the performances the audience of the Interferences Festival was invited to see, what’s the purpose of such a selection?

In the samples we demonstrate how crucial it can be to put great attention to visual dramaturgy in order to stay lively and challenging for the spectator’s eye. Every artist is perhaps aware that the surtitles are the only way to convey the basic meaning of a plot (when there is one); but not all of them are making use of all the numerous other communication elements in an equally successful way.

Margarita Mladenova and Ivan Dobchev’s attempt (sample number 3) is outstanding since it shapes a great part of the narrative on the performers’ physical features, on their gestures, their position under lights and a sharp management of proxemics. Appointed to lead the attention, during the choral parts, is not really the meaning of the single sentences (that still are very accurately edited), but rather those inflections, accents, accelerations and slowdowns that colour the speech. Ultimately, a subtle mastery of the space that lights up different corners of the stage with different tones helps the plot to change set and ferries the text from one novella to the other. We are overlooking Gogol’s Russia and Ukraine and reading on a digital screen fragments of a rambling discourse, similar to the one of Diary of a Madman, that, as the last excerpt offered, surprisingly ends up sounding as the most coherent one, only because Mladenova and Dobchev provided us in advance with a handbook to their language.

The difficulties a foreign audience might have found in Șerban’s The Good Person of Szechwan are perhaps rooted in a too static management of the space and the choreographic patterns: the wide stage—two side wings providing all the entries and a crèche-like scale model of the city on the backwall, where the musician plays and sings—is almost empty and crossed by all the characters who walk in and out covering almost the same diagonals. If one lowered down the volume of the words and songs, the visual parade would appear to retrace similar schemes over and over, detaching the attention from the hues of the (very dense) text, and without offering any other handhold to the spectator.

Stepping back to more general considerations, even in an all so familiar Western society such as Europe, trying to cross the language barrier is always a hard mission.

Though here and there exaggerated in summing input to input and yet cleverly evoking disturbing sequences that in some ways catch the glance, sample number 1, Elektra, manages to export an intense theatrical experience because it goes beyond the plain delivery of a text.

Still, the solution found by Jaram Lee remains the most successful. Gently (yet smartly) tickling the fascination for exoticism, The Stranger’s Song accepts a basic compromise to export its language: to knead together a secular national tradition with certain easy communication tricks.

The storytelling itself is not only performed but discussed in front of the audience: Lee frequently steps outside the performance to explain why she uses the fan, why she needs a specific quality of attention and concentration, why she chose that single “very Western” story. If this style needs neither justification nor any special knowledge about Oriental cultures in order to be understood, it is perhaps because its communication elements were accurately prepared before exportation; their selection is already clear in the form and in the attitude of the performer, who cheerfully shares it with the audience.

In other words, a good strategy for an artist to attract and keep the foreign audience’s attention is to put all the elements to the test before exporting a play. As seen during the Young Journalists on Performing Arts think tank—where every topic had a different impact depending on the country—one needs to be extra careful when it comes to talking to a group of foreign colleagues: we don’t want to talk over people; it’s about listening and learning from one another.

Published on 22 December 2017 (Article originally written in Italian)