The Pursuit of an Alternative

The whole floor is flooded with two inches of water. A multi-coloured mountain is centre stage. A stack of clothes stands for a stack of bodies. This is the opening image of Lampedusa, Anders Lustgarten’s play at its German premiere directed by Olaf Kröck.

Stefano is a Sicilian fisherman who, since the boats have begun landing on the shore of the small island, is appointed to “fish out” the terrified survivors or their drowned bodies. Denise is a payday loan collector from Leeds. The actors are on two opposite sides of the stage; the characters they represent are separated by different backgrounds and hundreds of kilometres. What brings them together is not the refugee crisis but rather what this tragedy represents: the sense of hope photographed as it struggles to survive.

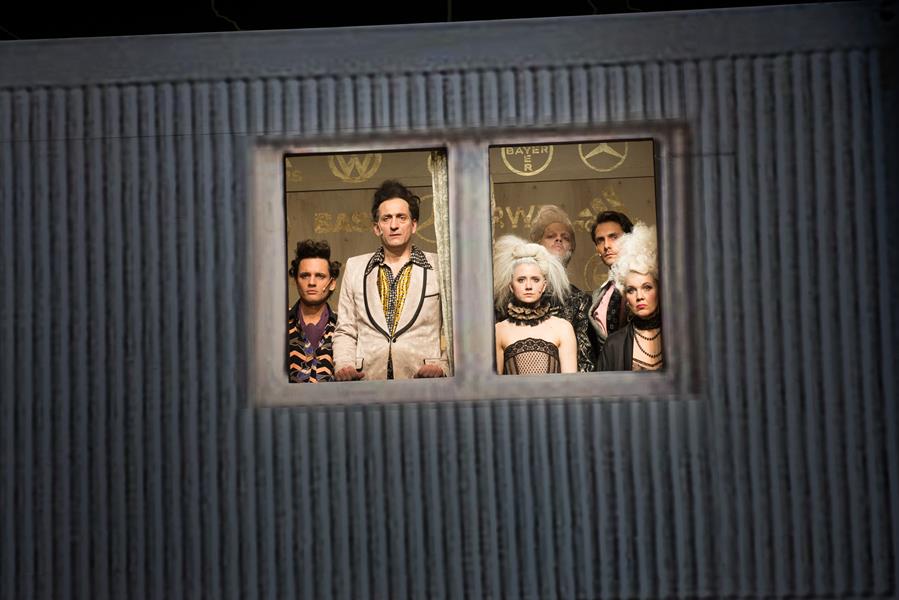

In programming the themed month The Own & The Foreign, the Schauspielhaus Bochum completed some remarkable juxtapositions, as the one of Lampedusa and Elfriede Jelinek’s The Suppliants / Appendix / Coda / Epilogue grounded, a play in four episodes that reflects on the refugee crisis with a rigorous analytic method, typical of the Austrian Nobel Prize laureate. Acquiring the title by the namesake Aeschylus’ tragedy in which the Danaids seek asylum in Argos, The Suppliants is an acidly ironic invective against the current European asylum policies that puts together actual facts and figures, numbers and moral statements to create a post-dramatic Golem of the language. In the presence of such a multi-layered and wordy text, filled with data, details and double entendres, it’s undoubtedly hard to find a space for any outstanding mise-en-scène solution. Yet, Hermann Schmidt-Rahmer’s direction and Thilo Reuter’s stage design—a concave map of refugee routes as a ceiling from which baby dolls pour down—enriched by screens and video projections, manage to keep the scene still but alive. Contrary to Lustgarten’s, Jelinek’s architecture of thought needs no characters: the actors, even though operated as marionettes and mouthpieces, succeed in giving back the power of the text through frenzied interactions and crazy costumes (designed by Michael Sieberock-Serafimowitsch).

It maybe interesting to confront Schmidt-Rahmer’s words spoken at the Café Europa roundtable and an excerpt from a Jelinek interview: one said that “theatre has to talk about things that we don’t know how to deal with”, the other: “I force the language to tell the truth even against its own will, a kind of truth that is present in the language anyway; where the language is keen to lie to us, I forbid it.”* As in any proper political form of theatre, in both the author’s and the director’s view, the short circuit seems to be completed by the audience that is forced to consider even the most unpopular perspective. From a point of view distorted by Euro-centricity, the lives of the migrants might really be worth nothing more than a pile of lifeless dolls, or a stack of abandoned rags.

And thus goes a line from Lampedusa: “Our glorious leaders want the migrants to drown, as a deterrent, a warning to others. If those men in their offices knew what we were coming from, they’d know we will never, ever stop.”

At the Café Europa roundtable, Anders Lustgarten talked about the intricate and unpopular political debate around the theme pointing out a precise cause: “The absence of a story.” To face such a bulimic flow of information and the consequent exploitation by the media and the political parties “an alternative story” should be created, to reinvigorate “the possibility of an agency,” without which the raise of “any kind of hope becomes impossible.”

As well as being a playwright and devising drama courses for prisoners, Lustgarten is committed to activism, a practice that he defines as “highly horizontal, that does not believe in leaders.” Indeed, his play Lampedusa can be seen as an apologue about the essence of activism: both of the two very different personalities walk the thin line between a moral commitment that comes from an emergency situation and the atavist fear that comes with an unexpected responsibility.

Stefano finds himself withered by the passiveness with which he performs his forced assignment; Denise’s task puts her in a dominant position and, at the same time, that very expression of power might drive her to an ethical dissolution. Almost unconsciously they both seek redemption, one by rescuing the wife of a survivor, the other by coming to terms with a long-last rift in the relationship with her sick mother.

Such a game of mirrors follows a rigid and cruel structure in Lustgarten’s text—with the two characters exchanging looks only at the very end—while Kröck’s staging builds up an invisible bridge between Stefano and Denise. Even though their paths never actually cross, the two of them share a repertoire of desperate gestures, splashing in the water, picking up the floating rags and even kissing each other. The text alternates Stefano’s simple but insightful tone with Denise’s thick dialect and ill-concealed anger, giving the two intertwined monologues a verbal rhythm that the actors—framed in a well-lit but immobile space—are not always able to revive in the performance. On the other hand, this general paralysis, broken in the final scenes, resonates in the broader discourse brought up by the British author: these two personae are in search of an alternative story. The possibility of agency requires the ultimate responsibility, the active role of an “own” towards the faraway reality of the “foreign”.

Published on 19 April 2016 (Article originally written in Italian)