Young Bosnians’ Rebellion Resembled the Punk Rebellion

“I wish the production of The Dragonslayers inspired among the audience a sense of admiration towards a young man sacrificing himself for the good of others.”

Interview with Iva Milošević, director

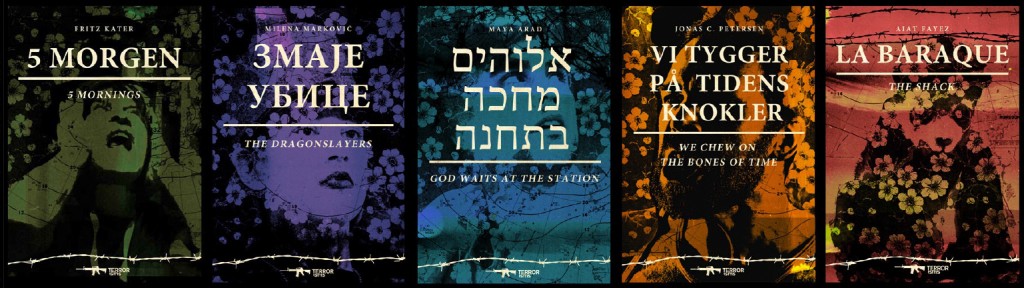

On Yugoslav Drama Theatre’s Ljuba Tadic Stage in Belgrade, director Iva Milošević is in the midst of staging the latest play by Milena Markovic “The Dragonslayers”, a play that artistically addresses the Sarajevo Assassination, Gavrilo Princip, and the Young Bosnians. The set is designed by Gorcin Stojanović, the costumes by Maja Mirković, and the music is composed and performed by Vladimir Pejković. YDT is going to realise the production of “The Dragonslayers” as a part of the project of the Union of European Theatres marking the centenary of the beginning of World War One. The premiere is scheduled for 7 June.

The cast includes Nikola Rakocević, Mirjana Karanović, Milan Marić, Radovan Vujović, Dubravka Kovjanić, Jovana Gavrilović and Srdjan Timarov.

B.T: The Young Bosnians believed life to be a work of art, they loved mankind intensely, even while despising it. What were the thoughts you had after reading “The Dragonslayers”?

Iva Milošević: Their rebellion reminded me of the youth rebellion of 1968 and of punk rebellion of the late 1970s. Both were primarily rebellions of the heart. That’s what the Young Bosnian’s revolt was too.

B.T.:Which of your personal experiences have you recognised in the play “The Dragonslayers”, or rather, what are the reasons as to why you’d like to see this play in a theatre?

Iva Milošević: I was shaken by the vast sorrow and anger which drove these high school seniors to revolt, to oppose this ‘dragon’ that endangers their dignity, their freedom, and puts them in a slave-like position. This ‘dragon’ they fight is not only personified by the tyrannical figure of the Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne, but also by all those who consent to injustice with their heads bowed down, be it for lack of courage or for personal gain. When one reads the play by Milena Markovic, one faces the fact that the freedom-loving spirit is an indestructible category that, every now and again, throughout history, raises individuals above the numbness and indifference of the many.

B.T.: We ourselves live in curious times, in a way reminiscent of the period when Gavrilo Princip and the Young Bosnians themselves lived. Who are Milena Markovic’s dragonslayers really?

Iva Milošević: They are young rebels, intellectuals, enraptured freedom fighters, idealists who come from great poverty and misery. They strive for complete emancipation, both for their need to affirm themselves as dignified human beings and for desperation stemming from their sense of having no future.

B.T.: The story of the Young Bosnians is also a story of freedom, social justice, anarchism. Why is the play about Princip so ‘hot’ in this day and age?

Iva Milosević: I think the reason for it lies in the fact that the petit bourgeois spirit and authoritarian character, the axis of today’s world, find any resistance actively opposing the limitation of individual liberties hard to digest. Particularly great scepticism and cynicism is stirred when this opposition involves self-sacrifice and empathy towards the imperilled.

B.T.: In your previous productions you examined how one gets to violence. Why it happens, where its origins are. What were the conclusions you reached in this step as a director?

Iva Milošević: The answer is simple. When someone is bending your spine to the ground, there are two options: either your backbone snaps, or you defend yourself.

B.T.: “The Dragonslayers” contain poetry and rhetoric and classical dramatic dialogue. How do you make all of this unified on stage? What are the heroes we are going to see like, considering the fact that Milena Markovic raised this tale to a mythic level?

Iva Milošević: It’s going to be a poetic show and I believe at times it will indeed work as a specific ‘heroic cabaret’ in its own right. It is going to be about the soul’s journey from righteous anger to heroic act, and paying the price for such life choices.

B.T.: What level of excitement accompanies your daily rehearsals of this play at YDT?

Iva Milošević: I am incredibly glad to direct this play and to have the very cast that I have. I feel a great sense of responsibility because we speak of young people who really existed, and because I am aware of the fact that amongst the audience there will be young people who came to see the play in search of answers to many important questions, such as the question of what it’s worth fighting for, but also the question of the price of the sacrifice for the general good.

B.T.: The story of the Young Bosnians has a tumultuous historical background. How do you view the different historical interpretations of the Sarajevo assassination and the Young Bosnians?

Iva Milošević: Revolt has always been and always will be a subversive topic. By this very fact it is subject to all manner of relativisation, politisation, appropriation etc.

B.T.: Have “The Dragonslayers” changed you and if yes, how?

Iva Milošević: Thanks to this play I got informed in more detail about the era and the Young Bosnia movement, of which, I admit, I had known very little.

B.T.: Who would you particularly like to see in the audience and why? What emotions would you like to convey through the play “The Dragonslayers”?

Iva Milošević: I’d be glad if the show attracts younger audiences, but I don’t see this as its most important task. I’d like it to inspire a sense of admiration for a young person sacrificing themselves for the good of others.

Go back to: The Serbian Press about “The Dragonslayers”

Published on 2 December 2015