S.O.S. Encapsulation… or the Soul after Victory III

The riddle of the International Theatre Festival is its name: Interferences. This year’s sixth edition of the biennial tournament for collective representations in Cluj-Napoca, which has been held every two years since 2008, deals with the theme of war. From the 22nd to the 30th November 2018, 16 ensembles from 13 countries met in Transylvania, a cultural interface below the Carpathian Arc since antiquity.

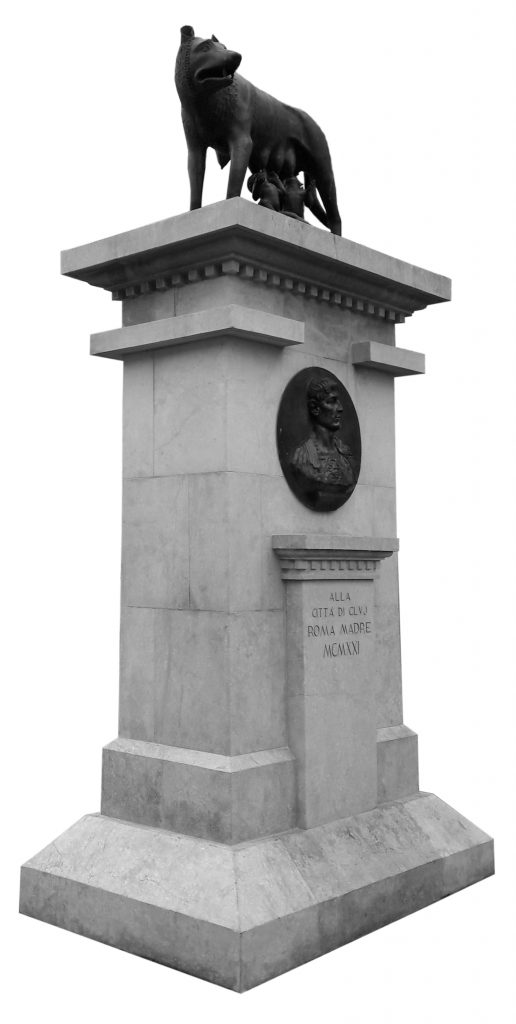

The cultural diversity and multilingualism can be felt at every corner of the city. It is home to various spaces of experience of distant pasts, which in their linguistic expression meets daily today in Hungarian, Romanian and sometimes also in German. The memorial culture of the city with the name triangle amazes and wonders visitors at the everyday overlays, because besides Cluj-Napoca there are also the names Kolozsvár and Klausenburg. Thus, the two city centres, a Hungarian and a Romanian one, are connected with each other by a street on which the sculpture of a myth was placed. It is the myth of the founding history of Rome – a she-wolf feeding Romulus and Remus on a marble-covered pedestal with a portrait of Trajan, including the inscription: Alla Citta di Cluj – Roma Madre – MCMXXI. The visitor is confronted with the question: Is this still young memorial a reminiscence of 1921, staging Rome as a matrilineal origin for the city of Cluj-Napoca?

Time is Convention

Anyone looking at the sculpture from outside looks for words to understand what kind of représentation finds expression here. Judging by everyday political standards, it may well have been the intention to create sense to meet the challenges after the turn of 1989/1992. However, a link to the founding myths of the nation-building process after Romania’s founding one hundred years ago as a result of the Versailles peace negotiations has attracted too much social attention. Festival director Gábor Tompa, at the opening of the festival in the Hungarian theatre of Cluj-Napoca, gives a hint, both in his address in the festival catalogue and in his personal address: the theme of the festival is war. One hundred years has passed since the end of the First World War, whose peace negotiations dramatically and tragically rearranged the map of Europe. At the same time, however, they also prolonged warlike conflicts indefinitely until today. – In his speech, he directly asks the audience the question: “How can we remember war in ways other than that losers remember losers? – Because in a war there are no winners,” says Tompa.

From the spectator’s point of view, his suggestion makes the facets of the festival programme comprehensible much more quickly. The chosen season in the festival calendar is the time of mental heaviness in Europe. Autumn passes into winter and the days become shorter. And outside only fog circulates. Theatre as a festival needs such a stable sacred anchor, which is realized anew in a periodic sequence depending on the season. The word “sacred” floats in my mind as I listen attentively to Tompa’s words in the auditorium as I leaf through the catalogue, creating a certain sense of time and space. I’m thinking of Henri Hubert’s essay on La représentation du temps dans la religion et la magie from 1904, read recently on my tablet. Those who get involved with the festival events leave the normal space-time feeling of everyday life. The sacred space-time order captures a feeling of infinity and immutability. Such a joint search for sense in theatre competes with the fixed memorial culture, which wants to present stability as an unchangeable factor for everyday life as obligatory; a demand that is strived for in everyday life, but rarely fulfilled.

The theatre, which has its origins in magic, has its own unfixed foundation of meaning. It is an open project, a search for sense. If one accepts the festival from the spectator’s point of view, one agrees with sacred space-time. Tompa’s choice of pieces is based on this common search for meaning under the sign of a shared time and a shared space when he writes in his address in the festival catalogue: With the various types of war, it is important to speak of a theatre of fright. The terrible trauma caused by violence would call for an individual and collective “exorcism”. The fixed point of the search for meaning lies in the similarity between war and theatre, for they are the reciprocal actions of two opposing forces.

Scrape That Fiddle More Darkly

The selection of the various directorial manuscripts from different theatre families in Europe stands for the side of change, self-assessment and collective responsibility. Absorbing a few festival days demands a higher level of attention from visitors from outside and the admission that they can’t see everything. The simultaneous presence of English, French, Romanian and Hungarian, the languages of the guest performances, such as German, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Lithuanian, Polish, Russian and Serbian, will also be added. There is a closely timed main programme in the main hall and in the studio. There is a supporting programme in the Tiff House, in the Tranzit House, in the Paintbrush Factory and in the Quadro Gallery. There are exhibitions and concerts. And for the first time there was a technical interference called Digital Hermits. This conference at the Tranzit House tried to explore the use of digital technologies and their impact on the coexistence of people in our world. A contribution on war that takes into account the consequences of the Cold War, when the Internet was born, to ensure communication between entities after a nuclear fallout. The focus was on user interfaces – also known as new media – and their own spaces of experience in and with time and space. It was seen as problematic that the dialogue between the generations leads to a dichotomy between the group of people who live completely without digital technologies and the group who no longer want to shape life without them. The connection of passions to the filter bubbles and echo chambers of the digital world unfortunately failed to materialize.

One question that has always been virulent for the two-thousand-year history of theatre is: How do people behave in war? – In a collapse crisis, laughter and crying not only alternate, they can also occur simultaneously. One person’s suffering is the other’s only short joy until the perspectives change and the persecutor becomes the persecuted. Milo Raus shows with his work Compassion. The history of the machine gun an impressice teichoscopy, to which the dramatic elements of the Greek tragedy are reduced. In it, this change of perspective is performed in a loop. The actress Ursina Lardi from the ensemble of the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz in Berlin plays herself as a young development aid worker in Rwanda, where she witnessed the Hutu genocide of the Tutsi. Later she finds out that the person she helped became the perpetrator. The Belgian actress Consolate Sipérus also plays herself. As a baby, she was adopted by a Belgian couple. More than the country of origin, Rwanda, and the catalogue with the baby faces that can be chosen for adoption are not known to her. From the viewer’s point of view, this enormous amount of social facts is hardly bearable. And Lardi tells of the theatres of war with impressive power of speech and physical presence, as if she has just observed this quantity of irrational actions.

By représentation, Hubert means exactly this sacred time level. Just as in the auditorium on my tablet I work on an over one-hundred-year-old text in order to pursue questions of understanding about what is happening on stage, Lardi and Sipérus create a public sphere. Not just a public speech act, that is, one that can be seen by everyone, is performed here, at the same time an understanding of the event opens up for other group members who are not directly involved in the actual action. Now and here we take an insight into the events that took place on another continent in 1994. This is the quality of the festival, with which the riddle of the name, Interferences, is solved: it is the coincidence of all time levels in the concept of humanity. The model upheld in Europe since the Renaissance breaks itself in the face of the horrors of precisely this persistent humanity, no matter what skin colour, language, culture or religion it claims to be right and good for itself. The Greek drama models serve this quality.

Anna Badora of the Volkstheater Wien (Vienna Volkstheater) has created a link between antique representational drama and post-dramatic attempts to cope with the European present in Renaissance style. She stages an Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides in the format of the Golden Ratio, in which Iphigenia is actually sacrificed at the end of the first part, with which the tragedy of Euripides, which for us has only been handed down as a fragment, ends. The war really begins with Badora. While the battle rages, we spectators go to the toilet or to the fresh air. From the two thousand years in the past we fall in the second part into the Syrian present. Here, Stefano Massini’s text Occident Express serves as the basis for a play for the same actors who are now making their way to Europe as civil society from the war zones in Iraq and Syria.

It is said that waves of crisis lead to a learning process. Gabor Tompa shows in his in-house production of William Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice that limits are inherent in this learning process. The fact that both actors, Gábor Viola and Zsolt Bogdán, can play both the role of Antonio and that of Shylock as respective double casts bears witness to the deep empathy for the characters that is necessary to represent sacrificial rituals. Antonio, whose sadness at the beginning may not be revealed to the audience until the end of the piece – at the beginning it is not business or love that causes his suffering – it is the quotations of the milieus and their internal morals made by Tompa in his soundscape installation, who let Antonio be as obviously sad as the mirror-inverted despair of Shylock, whose sacrifice in the end – analogous to Iphigenia’s sacrifice – is needed to restore that very internal morality after the group has gone through a common crisis. Antonio, like his alter ego Agamemnon (father of Iphigenia and at the same time commander who sacrifices his daughter), represents in this sense the permanent depression of a human being who knows that it always seeks the good, but at the same time always creates the bad.

Fatherland

The “exorcism” of the festival, which was the goal, took on a physically concrete form collectively and practically with the staging Vaterland in the choreography of Csaba Horváth and the stage design of Csaba Antal. The Forte Company presents text elements from Thomas Bernhard’s The Italians in a rhythmic and sporty sequence of scenes that gesturally play the timbres of Bernhard’s model. Bernhard, who in his will still wanted to ensure that no text, neither novel nor stage text, narrative or poem, would ever appear in Austria, was at war with the eccentric way of his fellow countrymen dealing with National Socialist traditions. The staging succeeds in allowing Bernhard to be regarded as the master of plastic surgery of collective passions that are unquestioned in memorial culture or devotional objects. Whether a geographical space is assigned a patrilineal or matrilineal original character is actually uninteresting.

In this way, the festival creates a concrete link to the themes of past years. Whereas in 2014, for example, it was still necessary to report on the stories of the body, this year the theme of war captures the passions in a way that suggests new approaches to the content of security policy measures, which are often difficult to understand in everyday life. The experiment on the formal side, such as Milo Rau’s, of exclusively exhibiting teichoscopy, seems all too minimalistic. We do not know whether the actress Ursina Lardi was really in Rwanda and whether Consolate Sipérius was really adopted. Here documentary theatre finds its limits in fictionality and has to compete with the classics, the timelessly valid dramas since antiquity. Mere indignation could perhaps have been problematized in connection with the digital filter bubbles and their echo chambers. But then the acting characters, whose limitations and weaknesses in Euripides or Shakespeare were excellently designed and presented in their plot constraints and intentions, would also have had to have been worked out more precisely in Milo Rau’s work. There are no spaces free of experience, even if the widespread contemporary encapsulation à la New Media and the generation conflicts associated with it might suggest it.

When a ship is rescued, the SOS emergency call is made beforehand and the bodies are rescued. The Interferences International Theatre Festival reminds us that the purpose of the SOS emergency call is to save souls. It demands their participation, a shared attention. An encapsulation in technical terms or as usual in analogue memorial culture, on the other hand, leads to isolation with fixed values of collective internal morals and their obligatory victims. By rejecting such tendencies of isolation, the theatre festival leads the search for meaning and sense in Cluj-Napoca.

Contrary to what the sculpture of the founding myth of the city of Rome and its staged history of origin suggests for Cluj-Napoca, the theatre has understood the origo principle. Florence Dupont can read about this punch line on the “monument” to Romulus and Remus: Rome – city without origin. The punchline is: there is no origin. There is only one diversity in mutual respect and recognition. This is what the origo principle stands for. Interferences is also the name for an unfinished search for sense. Theatre is and remains an open project, both in terms of content and form.

Published on 21 January 2019 (Article originally written in German)