Inheritance Will Kill You If You Do Not Reconsider It Every Day

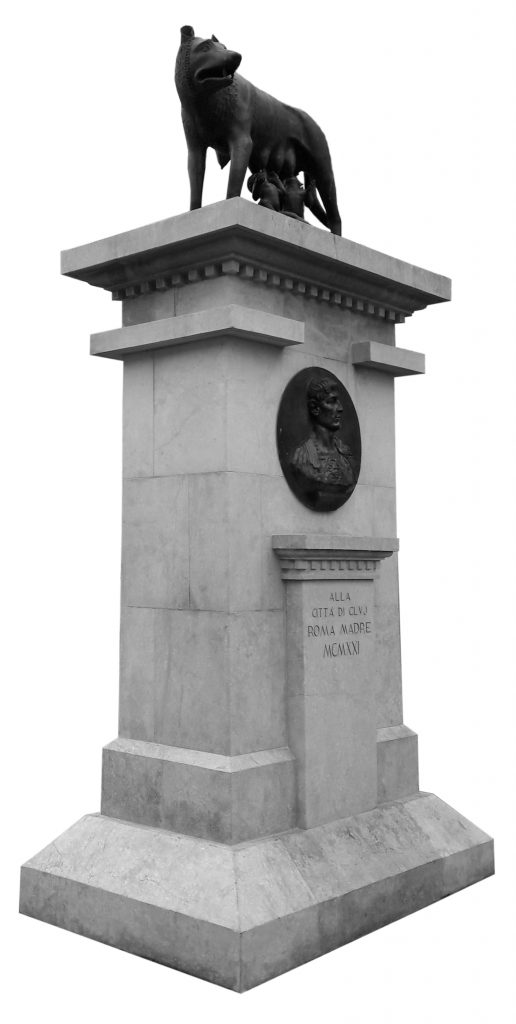

For 30 years now, András Visky (Hungarian-Romanian, born in Târgu-Mureş in 1957) has been the main dramaturg of The Hungarian Theatre of Cluj. He is a poet, playwright whose plays are staged across Europe and the USA, essayist, lecturer at academic institutions in Romania, Hungary and USA, who also coined and developed the barrack-dramaturgy[1] concept of theatre.

During the 18th edition of The Festival of the Union des Théâtres de l’Europe, hosted by The Hungarian Theatre of Cluj at the end of November 2019, Visky was responsible for leading and moderating the post-show talks with the teams of each production. The sessions lasted about an hour and always begun with an insightful, heartfelt introduction, after which everyone was included in the conversation by asking the right questions. The post-show talks were led in such a delicate, dedicated, distinctive and delightful manner, that they quickly became for the audience and the festival guests just as expected as the performances themselves.

During the last days of the festival, Ina Doublekova met with András Visky to talk about what has been discussed and seen during the festival and what was left unsaid, as well as about the past and the future of culture and theatre and the role of transnational alliances like the UTE.

Union des Théâtres de l’Europe (UTE) was founded in 1990 – the same year when you became the dramaturg of The Hungarian State Theatre of Cluj – with the aim to establish artistic links beyond the still-standing walls after the 1989 changes. What kind of bridges do we need in Europe today?

If I try to answer this question from the point of view of UTE, I think that it has lost its identity, because its goal has been fulfilled. The idea of constructing bridges between Eastern and Western Europe to help through cultural means the European integration, in many aspects, has been achieved. Which is great! When an institution or an artistic umbrella like the UTE can declare “we achieved our goal”, this is great. But on the other hand, it creates a vacuum. If the UTE would like to survive, it would need a new definition of its mission. And this will not be easy because this is never easy. On the one hand, there is a very rich inheritance, a very important legacy, and on the other hand, the UTE has always been progressive. Now, what does it mean to be progressive? In my opinion, one of the most fragile aspects of Western culture is essentially Western inheritance.

I think that this is also true if you look at the European Union – as a political formation it has been and still is very important because it has avoided war, it has avoided the falling apart of the continent after the changes that 1989 brought, and now the question is: to expand or not. From the Western point of view, there is angst about it, from the Eastern part, there is an expectation to make brave, courageous steps.

How has the role of the dramaturg evolved over these 30 years during which you have been holding this position and what does it represent today?

I think that one of the major changes in contemporary theatre is related to the dramaturg. He is connected to the director, whose status would still maintain this classic-modernist instance of the father of the performance. This modernist legacy of fatherhood is going through major changes, which the dramaturg has already experienced on a daily basis. As I explain in the chapter ‘Barrack-dramaturgy and the captive audience’ which I wrote for The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy in 2014, the daily practice of theatre requires a dramaturg who is prepared in various ways. The Hamburgian dramaturg has now become a writer, a moderator in the devised theatre, a video editor if we consider the video as an essential part of contemporary performance, and that means that this person needs to be an expert on the digital, while also helping the press officer, moderating the post-show talks, etc, etc. I have developed, I hope, my own style of doing those sessions because I do consider that theatre is something serious.

What do you mean by serious? And how do you see the place and role of theatre in our contemporary world?

Theatre in this post-religious era that we are living in is maybe the strongest and the unique institution that can literally gather people together and offer the public a collective experience. It offers a real dialogue and understanding of ourselves. As you know, my concept of the dramaturgy is connected to the prison. My first childhood memory is that I am a prisoner in a setting[1] which is really absurdist in so many ways. It helped me realize that theatre can offer the means for individuals and groups to tell, express or reenact their own stories. So, for me, theatre as space is a prison but we enter into this prison by our own free will and the experiences we are going through in this prison can set us free. And the keyword here is freedom. And why am I saying this? Because somebody who is imprisoned lives a double life. For that person, the prison is never an immediate reality. The immediate reality is in the future or in the past– when I was free and when I will be free.

Researching this idea, I found that in our culture, which is controlled by the media, we are also imprisoned because the media creates for us a virtual life which is always in the future: if I get this, I will be happier. Or we want to live in the body of a celebrity. The media creates this kind of virtual bodies and we want to step into them. That is why we are experiencing so many changes of identities.

Our willingness to be what we are is covered by many things and theatre could be a tool to recognize ourselves as ourselves. And to accept ourselves as we are. To consider ourselves as a unique event in the life of the Universe. The theatre can give us a very special strength – to eradicate this sorrow that “I am not like the other”. You do not need to be like the other. And to understand and accept yourself with joy, because my freedom should be fulfilled by myself. Nobody else can fulfil my own freedom. And this way I can be a part of a community. If I am not a free person, I cannot be part of a community in a responsible, useful way. Because nobody needs a person who is not free and who is dependent on many things.

After 11 years of interruption, The Hungarian Theater of Cluj just hosted the 18th edition of The Festival of the Union des Théâtres de l’Europe, presenting nineteen performances from members of this prestigious network, which has been recognized as a Cultural Ambassador by the European Commission. Four of the productions were based on contemporary playwriting – “Concord Floral” by Jordan Tannahill; “The Elephant” by Kostas Vostantzoglou; “I/FABRE” based on texts of Jan Fabre; “How to Date a Feminist” by Samantha Ellis – while the remaining fifteen were based on or were interpreting a text by established, canonic names such as Bertolt Brecht, William Shakespeare, Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg or ancient myths. Was this dramaturgical landscape of the festival surprising for you in any way?

That was not a surprise to me but with this question, you are touching the core of the inner conflict of UTE. The esthetics of this network is post-Post-Brookian, which has big masters and works only with classics. Silviu Purcarete has said it many times that he needs to work with a text which has settled down. Now the question is: is this kind of theatre updated? What would be a progressive approach to this legacy? When the inheritance is very rich, it could become a huge burden. A legacy becomes a burden when we are worshipping it. Being critical to it in a creative way is the only chance of reborn. And the members of UTE know this, that they are now in the in-betweenness of the very rich past and the future, which is not seen. And to exit it, the network will need an open dialogue and to bring in the young creators, who would approach the idea of theatre in a very contemporary way. For me, the ideal version would be to handle the progressive need for doing theatre and the big legacy without hysteria, as I am convinced that inheritance will kill you if you do not reconsider it every day.

Furthermore, the theatre lives in the present time, it is a discourse about the present time. We are living either in the past in a nostalgic way, or in the future, which is the virtuality of our existence. And I think that the theatre addresses the realm of the present time and we are living the present when we are not reflecting upon it. When we are going through a real experience, it is a transformative experience. And transformation is not something mysterious or mystical, it is the anagnorisis in the system of my society, of Europe, of the World, as we are living in an endangered world – languages are endangered, communities are endangered, nature is endangered, etc., etc. And the theater has always been the discourse about the fragility of the human being. That is not a fiction.

Yet, it feels that exactly this very contemporary fragility of humanity, the pressing global issues such as climate change, for example, often fail to be reflected in a daring way in this Post-Brookian theatre form, as you defined it, which is still the dominant form of theatre-making. And this weakens the role of theatre in society.

The inner tension here is between the metaphorical method, symbolic on the one hand, and the performative, which is so immediate, on the other hand. The question is if there is enough intellectual, spiritual, creative power to address these issues. And there is enough of it in contemporary theatre for sure, I have seen many experiments. However, this is not a mainstream theatre. The inner conflict is again that theatre is always about buildings, about architecture and architecture is about legacy. Yet, the daring contemporary theater has chosen to work in intimate spaces.

Clearly, part of the reasons for this choice is also that the politicians and funding-bodies still recognize more easily an established structure and the larger proportion of funding goes to those buildings and institutions.

The political discourse is unavoidable because speaking about the present time in a responsible way means that you are doing a political type of theatre. The politics is always included but there are many ways in which this could happen. And this is the role of organizations like UTE – to address the freedom of theatre from the political framework. I believe that art in Europe should be subsided but not to be controlled by these subventions.

Talking about politics, legacy and major current topics, the most heated debates during one of the post-show talks you moderated erupted after the performance of “Danton’s Death” of the National Theatre São João from Porto on the questions of representation of women and their role in theatre. Nuno Cardoso, the director of the performance, stated: “We cannot hide it, we live in a patriarchal society. Point. There is no discussion about that. If you take all the heritage of Western drama, you have great actresses and great female characters, maybe the best characters are female characters, but it is always tilted to a man. And it is an issue we need to deal with now.” In your opinion, how can we deal with it in a fruitful way, without falling into harmful extremes?

In the contemporary Romanian theatre there are more and more female directors. Here, at The Hungarian National Theater of Cluj, we announced a competition for young directors. And we offered all our theatre’s resources to the projects we liked. Out of five selected projects, three were submitted by women. Two of those projects are already happening, they are running, and the third one is going to have its premiere in mid-December. So, I do not want to mix my ideas of value with political issues, but I think that we have to find different ways to attract women, to gain their trust, in order to submit their projects, to be part of the image and the landscape of theatre.

I think that this competition has been very fruitful and could be a working model for many theatres. But of course, you have to take risks. Not only because of the women, but mainly because very young directors are submitting their projects, they look very well on paper but you do not know if they might reach a flop. But still, what is the problem? The flop is part of the development. And I like to be part of these processes; I always lead the open discussions between them and the audience, press, etc. We have to work to trust each other more and more.

At The Hungarian Theater of Cluj, you have a different approach to the technicians as well – the audience of the festival saw three of them playing in the opening performance of “Mother Courage and Her Children” (co-production of The Hungarian Theatre of Cluj and Staatsschauspiel Dresden, directed by Armin Petras) and one in “A Doll’s House” (production of The Hungarian Theatre of Cluj, directed by Botond Nagy). Can you tell us a little bit more about that?

I am very interested in the theory of photography, though I haven’t taken a single picture in my entire life. However, I once curated a photo-exhibition in our theatre. The photographer was Nelson Fitch, a very young American artist who came to me to make a project. So I asked him to work on this project, “The Invisible Theater”, to follow the technicians, to show how they construct and how they deconstruct, what are these invisible people. I call them “the angles of the performances”. The exhibition was very beautiful and the technicians felt honored. Afterwards, Nelson presented to all of them the photos in beautiful frames.

We invite them as actors in different performances; it has happened many, many times, so for our theatre to welcome the technicians on stage is not a special event anymore. Also, there is a very famous staging of “A Midsummer Night’s Dreams” by Alexandru Dabija (the performance opened in 2009 at the Odeon Theater in Bucharest, Romania – A/N) with the technical crew making the scene in the forest, which was amazingly beautiful, very strong and very warm, it was a big surprise.

What kind of impact do you expect this festival to have on the inner life of The Hungarian Theatre of Cluj and on its presence in the city?

I believe that this festival is very important for Cluj. Our city has grown in the past years dramatically from 120,000 thousand people to more than 600,000, it’s a big boom. So the theatre plays an important role in the life of the city and I personally have thoughts and projects to try to approach this new community of inhabitants. Because I think that theatre needs to change its policy and not to wait for the people to come into the building but to go out and reach them in the in-between spaces.

Published on 26 March 2020

- Visky, András, ‘Barrack-dramaturgy and the captive audience’, in Magda Romanska (ed.), The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy, London; New York: Routledge, 2014

- In 1958, when András Visky was 1-years-old, his father, Ferenc Visky, minister of the Hungarian Reformed Church, was sentenced to 22 years in prison by the Romanian Communist authorities. Soon after that his wife and their seven children were deported to Bărăgan setting separately. The family was released in 1964 and reunited.