Harbour 40. On the docks of Europe

In the context of the 11th Short Theatre festival in Rome, four out of five playwrights involved in the UTE project Harbour40 were invited to read extracts from their new texts dealing with harbours and the people associated with them. Here’s a short report about such a multilingual and multicultural event.

Playwriting has never stopped evolving. From country to country, the art of writing for the stage holds a diversified relevance, depending on tradition and, at the same time, on cultural borders continuously pushing and shoving, on the ferment of certain themes, on emerging urgencies in a changing world. Because changing is the word—with its grammar, syntax and semantics—but, first of all, is the imagery; as if from century to century the need for representation had refused too fixed a structure in search of a model always able to reassess the live presence of the spectator, which is to be considered as an ungovernable cell of an organic process.

And that’s how writing acquires temporal and territorial peculiarities, that’s how the “classics” are born, that’s why a text might turn out “old-fashioned” or “out of context” rather than “revolutionary” or “suitable” for a certain time or place or audience. Most of such dynamics change as soon as the paradigm of the “lonely writer” is subverted.

Harbour40 is the title of a project developed through a schedule of meetings and think tanks held in the context of the “Conflict Zones / Zones de Conflits” project by the UTE in Rome and Vienna. Playwrights from Bulgaria (Stefan Ivanov), Greece (Angeliki Darlasi), Italy (Roberto Scarpetti), Palestine (Amir Nizar Zuabi) and Syria (Ibrahim Amir) have been discussing burning global issues, and how those relate to their societies. The brain-storming generated the idea of writing collectively, while on the other hand trying not to drop the fundamental specificities attached to each political and cultural background.

With the technical support of the Teatro di Roma and thanks to a very enthusiastic participation of the staff of the Short Theatre festival—directed by Italian director Fabrizio Arcuri since 2006—the first outcome of Harbour40 was a public reading at La Pelanda, a former slaughterhouse converted into a cultural venue in Rome. The excerpts presented by Angeliki Darlasi, Stefan Ivanov, Roberto Scarpetti and Amir Nizar Zuabi, though read in five different languages, had many things in common, and a shared leading image: the harbour, imagined as a “non-place” where people leave and return; where they meet and exchange goods and words, even lives and destinies. The further steps of the project would aim to collect the four texts and mix them into a comprehensive structure, letting the story fly from Jaffa to Piraeus, from Genoa to the Black Sea, but also through markets in the Syrian desert, Turkey and Tunisia.

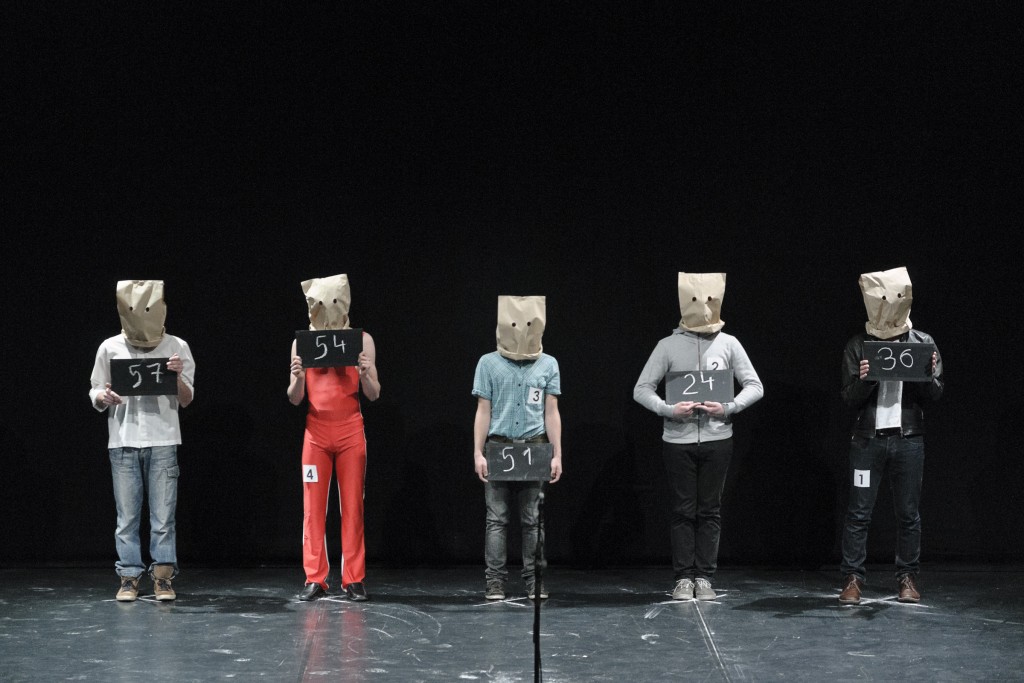

On a bare stage, the four authors sit on a black couch under a dimmed light; crossing a delicate fog, each of them takes turn at the microphones placed on the front stage. When one rests the pages on the bookstand and starts reading, it’s like being left alone in another world.

Ivanov murmurs his Bulgarian lines keeping his body perfectly still, the surtitles stream on the screen and tell about a grandson and a grandfather, they talk about the channel that links Sofia and the Black Sea, that cost 22 thousand deaths among the prisoners from the Gulag.

In Darlasi’s fragment, Iliana walks back and forth on a dock of Piraeus, waiting for somebody; Natasha is fishing: the tragedy of the refugee flows is narrated from the point of view of the passengers, while the fate remains uncertain even when the boats touch land, and a life might change in unpredictable and painful ways.

Scarpetti’s monologue is the account of a trip to Genoa, where a Tunisian man is sent by the family to sell the house of a dead uncle who had left Tunisia many years ago: the infernal Italian bureaucracy will swallow him, scaling down any expectation about a fortune to be made in a foreign country to which many compatriots would love to escape.

Nizar Zuabi imagines the interview between different port-authority officers with Miss Queen, who is in search of her disappeared father. Beyond obstructionism and the suspect of an intentional code of silence, the father himself appears as a sort of Shakespearian vision, speaking Arab and whispering some chilling details about his—most likely deadly—trip.

More than any other form of writing, a play lets the characters speak up with their own voices, and the main task of playwriting should indeed be to deal with actual facts, bringing the inner feelings to the surface.

Just before the reading, the festival organized a public meeting held by the journalist Graziano Graziani, in which the four authors sit with Italian and French colleagues (Erika Z. Galli, Martina Ruggeri, Lorenzo Garozzo, Alessandra Di Lernia and Sonia Chiambretto), members of Fabulamundi Playwriting Europe, a networking programme for translating and diffusion of European plays. The discussion focused on the question of language and what kind of audience a playwright might (or should) fancy. Although attempting very different approaches, the quasi totality of the writers does not want to imagine an ideal spectator, in order not to feel too comfortable and rather drag the audience into a realm as uneasy as the contemporary issues they deal with.

When asking questions to the spectators of Harbour40, the strongest feedback was of course on the themes, on how Europe and the Mediterranean mirror the contemporary social-political contradictions. But for such a project it’s also important to take note of some other comments that expressed how fascinating it was to listen to multilingual texts without the mediation of the actors, but rather facing the very presence of the author. Also because of the fact that the audience was largely composed of professionals, a great part of the attention was focused on the body, on how the absence of the mise-en-scène brought the very essence of the words (with their peculiarities in linguistics and spelling) on the top of any form of theatrical interpretation. Thus, Ivanov’s firm and polite immobility could be confronted with a more animated and “acted” performance delivered by Nizar Zuabi, deriving from different professional backgrounds but also from cultural specificities in terms of language and expressiveness.

If, on the one hand, the term “collective” indicates something that is done together, its roots go down to the act of “collecting”, as to say to grasp bits and pieces of identity, displaying them in front of an active and diversified audience, that shapes a myriad of, both personal and universal, meanings.

Published on 22 September 2016 (Article originally written in Italian)