THEATRE OF DIVERSITY

When it comes to continuous activity, the Czech theatre represents one of the relatively young members of the vast and diverse European theatre structure. Beside a long-lasting tradition of puppet and folk theatre, its beginnings extend to the second half of the 19th century, a period when the first thoughts on constituting the independent Czech State were formed. Since then, professional theatre has gone through major progress depending on geopolitical changes. First, there was the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, followed by the era of Nazi occupation throughout World War II. Then the socialist political turnover, lasting more than four decades, replaced by the long awaited process of democratization and the opening to global multicultural trends. These are significant factors that have influenced and shaped Czech culture into a blend between western and eastern ways of staging and artistic approaches. Now, current alternative theatre freely follows post-dramatic principles, whereas numerous theaters of public service continue to benefit from the classical repertory.

Once we leave out qualitative evaluation, the National Theatre in Prague is one of the most frequently discussed theaters in cultural and social areas. This is due to several mutually connected factors: the national-constructive function, which was fulfilled mostly at the begging of the Czech National Revival in 19th century; its complicated history throughout the first half of the 20th century, facing the changes of economic and ideological character; and last but not least, the artistic work of various figures (directors, actors, playwrights, set designers).

Nowadays, the National Theatre is defined in this multifunctional way even by law. It is classified as a symbol of national identity, a holder of national cultural heritage and a space for free artistic

work. Its focus is not just theatrical, but also on exhibitions and educational activities, with a need to succeed in a Czech and a European context alike. Regarding its connections abroad, the National Theatre became part of the Union des Théâtres de l’Europe — the international theatre organization that initiates work partnership among mostly European theatre creators, an exchange of and reflection on contemporary methods of staging, as well as a long-term intercultural dialogue with emphasis on young creators.

From the public’s perspective, the role of the National Theatre is a bit more problematic. It stands for an idea, where many spectators (or even citizens with little theatre experience) can project their frequently distorted visions of the National Theatre’s role. This issue is related to the mythical origin of the theatre in the era of the Czech National Revival. The infamously fixed idea, in which the newly formed Czech nation financed the rebuild of the national symbol (the first building burned out shortly after its opening) contrasts not just with historical facts (the contribution of the common people was merely symbolic, according to one from the emperor or a dominant German nobility), but also with the theatre’s official status itself. In fact, the National Theatre was a private capital company lead by wealthy members of the association who were deciding the repertoire.

Today, the National Theatre is the only Czech theatre financed by the state. It is often mistaken for a traditional platform that is supposed to stage only the classics (that suit the majority).

Looking at this issue of how to perceive and evaluate domestic theatre work, it is crucial to describe Czech theatre structures of the 20th century in general.

Throughout the era of socialism (1948-1989), all theaters were founded, controlled and shut down by the state. Art was censored by two institutions — the Ministry of Culture and Enlightenment and local authorities —, and officially stood for spreading the propaganda and strengthening the socialistic conviction. Fortunately, these restrictions were not manifested consistently in real life, but mostly during certain politically escalated times, especially in the mid-50s, when the socialistic idea was strictly established, and throughout the years of normalization during the 70s that lead back to tightened censorship and reinforced totalitarian regime. The Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 demonstrated violent suppression of the creative expansion in all fields of art during the 60s, as well as paralyzing the multicultural development for another two decades.

1989 brought the long-desired democratization of society, the possibility of private enterprise and of course the logical consequence of restructuring of the Czech theatre system. Most of the existing theaters, aside from the National Theatre, fell under the administration of municipal authorities. Next to these nonprofit theaters with a general cultural and educational mission, entrepreneurial theatre productions and theatre associations (incorrectly labeled as “independent”) started to evolve. They considerably enriched the cultural supply, even though they partly destabilized previous dramaturgical methods and lead to a general audience crisis. The 90s opened up space for experimenting with new forms (that were, at that time, already mainstream in the Western part of Europe; such as site-specific, immersive theatre, performance art, forms combining several genres and narrative methods), brought a commercialized type of theatre production (such as huge musical houses or stand up comedies), and general freedom of creative (self)expression. On the other hand, it also questioned previous methods of staging in the area of drama theatre, based on shared knowledge of togetherness between creators and spectators against the totalitarian regime, common understanding of performance, which was perceived primarily as an interpretation of the theme contained within the play. It was due to this destabilization of current staging principals that the new wave of directors and playwrights (Petr Lébl, Vladimír Morávek, J.A.Pitínský, Jan Nebeský) was enabled to profile themselves. Thanks to these creators, whose work was based on postmodern narrating principles, the ‘new’ vision of theatre started to be acknowledged by the public. Repertory theaters adopted — to a certain degree — alternative methods of staging that were previously typical of theatre studios and experimental stages, where these creators mostly debuted.

During the 90s, a festival network started to establish along with individuals, such as for instance, the Tanec Praha (since 1989), the International Theatre Festival Pilsen (since 1993), the Theatre European Regions (since 1994) or the ‘Prager Theaterfestival deutscher Sprache’(since 2000), with the aim of presenting performances from domestic and foreign creators on an international level. Festivals such as Skupa’s Pilsen or One Flew Over the Puppeteer’s Nest, organized by UNIMA (Union Internationale de la Marionnette), reflect an area of the puppet theatre. There are also shows (Přehlídka ke Světovému dni divadla pro děti a mládež) that are strictly concentrated on a children or adolescent audience of different age, which have been regularly organized since 2001.

Theatre censorship—typical of the years of socialism—ceased to exist once the new democratic government was established. Despite this welcomed turnabout, theatre struggled and still struggles with several limitations, however they no longer have a form of ideological restrictions. For example Ovčáček Čtveráček, an incorrect political satire presented in the city-run theatre Zlín, stands for an example of quite free self-expression on stage. Its creators were explicitly mocking spokesmen of the Czech president by assembling his own statements into a compact scenic form; other real-life political figures and cases were not left out either. Despite its regional background, this particular piece of theatre successfully gained national reputation, thanks to its aim to target contemporary phenomena. The success was so huge (also due to its uncritical support of the media) that the last performance was broadcasted live in selected cinemas.

Today’s creators are facing a different kind of restriction, an economic and financial one.

The transformation of the Czech state from a socialist to democratic one, on the one hand, lead to decentralization of the theatre monopoly and the strengthening of an autonomy of the troupes across cities (Ostrava, Brno, Hradec Králové, Plzeň). On the other hand it also contributed to poor financing conditions and the already problematic maintaining of theaters in low cost regions that were no longer predominantly supported by state budget.

The increasing demands on high-quality art projects—one of the crucial, yet very subjective criteria to grant particular theatre activity from regional or state funds—accentuated the lack of resources through the following years. Nowadays, there is no real law that would clearly define ways of supporting production from public funds.

Nonprofit organizations providing public service (museums, galleries etc.) have to apply for grants in various intervals, mostly every few years. Such processes come with certain difficulties, as long as managing public funding depends on non-objective reviews of committees which consist of experts of various specializations. This wide range of professions guarantees that not only aesthetic criteria are taken into account but also economic ones when it comes to subsidizing the cultural field; however it doesn’t necessarily apply to the impartiality of particular individuals and their personal interests. Only recently, in February 2017, did we see such an example, when the City of Prague decided not to provide a four-year grant to DOX, the Centre for Contemporary Art, one of the most progressive nonprofit institutions outside the historical centre, without providing any reasonable argument.

Nonprofit theaters of public service as well as independent theatre groups are similarly subsidized (systematically/on one-time basis) with public municipal funds, by higher regional units or even European Union institutions. Sponsors also play a significant role in the process of funding since they support public theaters as well as private and independent theaters. In addition, “independent” theatre groups derive their sources from a richly structured grant system. In general, multi sourcing is the most common method of funding, guaranteeing regular theatre activity and all kinds of productions.

Basic framework of the theatre system:

• Theatres established and run by state or self-governing institutions.

• Theatres of public service (mainly former regional theaters consisting of several departments like drama, opera, light opera and ballet: a model adopted from the German speaking area).

• Private theatres.

• Theatre groups (mostly amateurs, although current legislation doesn’t legally differentiate amateur theatre from professional theatre, since both types benefit from nonprofit support. What really distinguishes them is their functions).

The Czech theatre structure is dominated by drama theatre with a permanent casts. Most ensembles consist of permanent employees of various ages, assigned equally in a sense of collectivity. It also provides a chance to regularly or once host visiting creators with no permanent engagement. This kind of freelancing relates mostly to young directors, dramaturgs or actors, who are mostly invited to regional theaters based on their previous school and extracurricular work. These occasional projects enliven the rather traditional repertory of public theaters, oftentimes made of classical pieces with little space to experiment.

Young creators frequently enrich the conservative programme of contemporary drama with unusual interpretation of classics or their own works. The repertory frequently includes plays of team members, mostly by dramaturgs and directors.

The phenomenon of ‘author’ projects, i.e. the staging of texts that are written in the process, is mostly concentrated in Prague where the strong theatre alternative started to evolve throughout the 90s and is still going on. Nevertheless, the term alternative has more than one meaning: the non-profit type of theatre that provides public service and is run by cultural interests; it also relates to innovative, nontraditional theatre methods that go beyond the standard.

Such a structure naturally correlates with a diverse audience taste and therefore different aesthetic demands. In this regard, the Prague theatre network represents an example of great theatre diversity, thanks to its high concentration of productions in one place. Each stage has its own established base of audience that either increases or decreases, depending on specific dramaturgical choices, creators or economical factors.

Stages like Studio Hrdinů, which occupies the vast underground space of The National Gallery, and Divadlo Letí, located in interiors of the Štvanice Vila, are the very inspiring examples of marginally defined dramaturgy, which attracts the attention of a wide audience thanks to their location. The aesthetics of these spaces as such fundamentally influence the final scenic form.

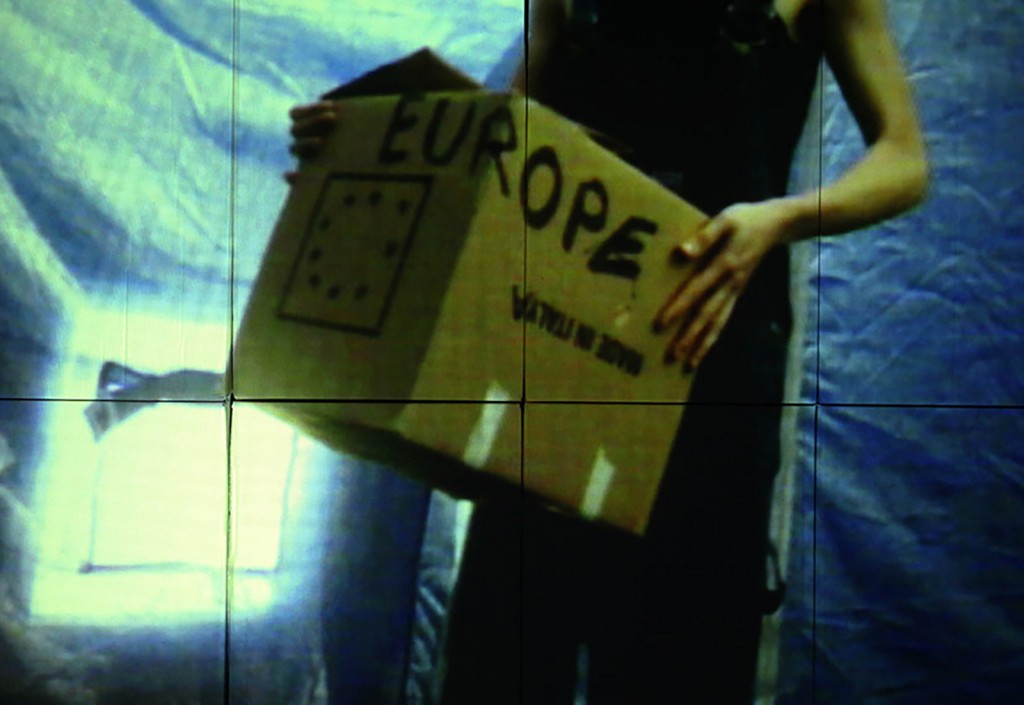

The creative collective of Studio Hrdinů, mainly constituted of directors and set designers Jan Horák, Michal Pěchouček and Kamila Polívková, focuses on the synthesis of drama with visual arts and multimedia devices. Through what are mostly ‘author’ projects, they are trying to disrupt common and standardized theatre forms, as well as the borders between theatre and art installation.

Together with the Divadlo Letí—despite their diametrically different aesthetics—they are examples of the contemporary theatre that plays an integral part in the social-cultural progress.

The repertory of the Divadlo Letí, which is lead by director Martina Schlegelová and dramaturg Marie Špalová, primarily consists of contemporary plays that have not yet been staged (for instance, Letí introduced the work of Mattias Brunn, Martin Crimp, Anna Saavedra or Lenka Lagronová). The programme is complemented by dramatic readings that are mostly focused on dramatic text, their structure and regular interpretation.

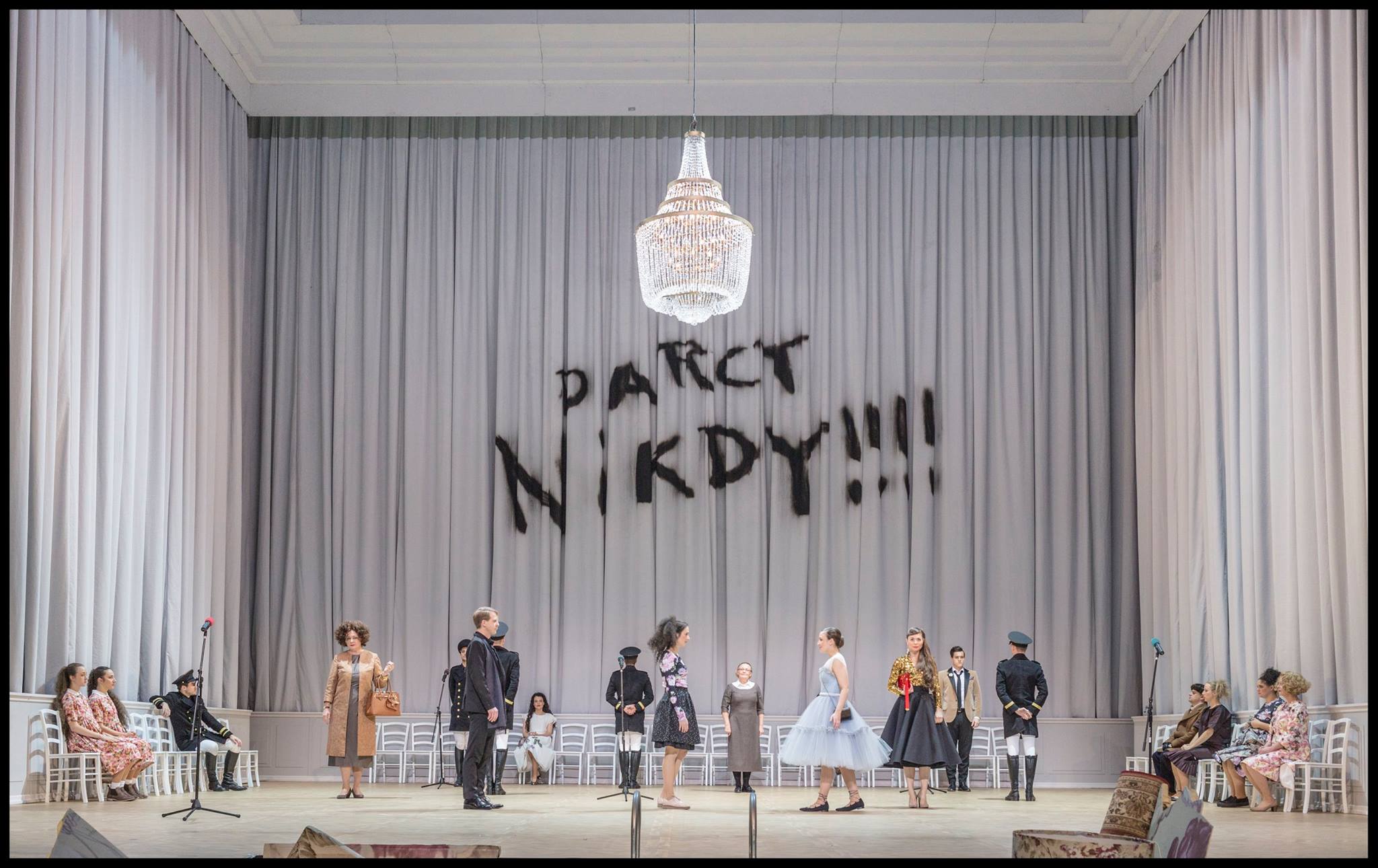

Even the National Theatre, which has been mentioned so many times, belongs to contemporary theatre, striving to deliver a theatrical experience that goes beyond the standard. Its artistic management has gone through fundamental changes in the past few years, and has successfully attracted vast media attention. It has been mainly after Daniel Špinar—a longtime freelance director who has worked for various regional stages—became artistic director of drama, that the attention of critics and a wide audience has been attracted. The new artistic department of drama with its programme ‘New Blood’ has brought a series of modifications, such as opening up the backstage area, accompanied with scenic action, and a radical opening of the ensemble to young actors and actresses, as well as a strictly formulated dramaturgy of each stage (the National Theatre consists of 4 ensembles; drama, opera, ballet and Laterna magika, occupying 4 different stages).

The dramaturgical selection for the historical building targets the conventional spectator, for whom it tries to provide modern art and a complex theatre experience (the one that is not associated with any famous star or any prestigious feeling). The repertoire of the main stage consists of classical pieces and adaptations of popular titles (e.g. Manon Lescaut by Vítěszlav Nezval or Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen).

The Estates Theatre features a high standard technical background, suitable for much more inde-pendent and courageous dramaturgy, which does not necessarily rely on a long-term viewers’ success.

The New Stage focuses strictly on a younger audience, attempting to attract them through the concept of the ‘alive building’: in addition to the stage, there are numerous venues like a café, gallery and a store, that promise potential attractiveness to those who associate the National Theatre only with the historical building and its history. The space is therefore full of projects of experimental character (The Mouse Experiment by the collective of authors, The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry) with a stress on contemporary drama.

Czech contemporary theatre is also made up of strong representatives outside the dramatic area, who try to explore the edges of (live) artistic expression. The experimental studios such as Farm in the Cave, based on the synthesis of the physical, dance and music theatre, or the dance company 420PEOPLE; they have both achieved considerable international acclaim and audience affection, mainly due to their systematic attempts to surpass theatre borders and their precise work on body language.

On the other hand, artists like Radim Vizváry (the performer responsible for the renaissance of mime arts) and Miřenka Čechová represent the leading figures in the field of physical theatre. Together, they established Tantehorse (the theatre company known for its strong physical articulation); they work either together or separately.

The Forman Brothers theatre, the nomadic fellowship with irregular ensemble, and Cirk La Putyka lead by Rostislav Novák, represent two aesthetically different forms of Czech contemporary circus.

The art group Handa Gote Research & Development holds a unique position when it comes to alternative methods, since it systematically explores the concept of post-dramatic and post-spectacular theatre, using all kinds of materials, both old and modern technology, the visual arts, as well as contemporary dance and music.

All examples mentioned in this article aim to outline the diversity of the performing arts in the Czech Theatre, combining traditional forms with more progressive, mainly Western European narrative methods.

NEKOLNÝ, Bohumil a kolektiv. Divadelní systémy a kulturní politika. Praha: Divadelní ústav, 2006.

DVOŘÁK, Jan. Kapitoly k tématu realizace divadla. Praha: Akademie múzických umění, 2005.

Published on 3 April 2017 (Article originally written in Czech)