German Theatre: Behind the Scenes of its Structures

The structure of theatres in the Federal Republic of Germany is characterized by a great number of theatres with a wide range of names: national theatre, state theatre, regional theatre, people’s stage, people’s theatre, residency theatre, municipal theatre, or also regional stages and open-air stages. These are ambivalent testimonies to past conditions in German history. Structurally speaking, the former court theatres have mostly become state theatres, where today’s state has taken over the responsibilities of the erstwhile court. The people’s stages movement is closely tied to the history of the workers’ movement. Today’s open-air stages not uncommonly had their origin as ‘thingspiel’ locations during the times of Hitler fascism. — This is a general overview of today’s constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany’s theatre structure.

Analogous to the different genres these theatres can have different branches, depending on size. We then talk about “multi-branch theatres” (Mehrspartentheater). These generally comprise ballet, opera and drama. In some cases, puppet theatre or children’s and youth theatre are also part of it. Oftentimes, the branches are also situated in independent theatres whose function is hinted at in the title, as in, for example, the Oper Köln (Cologne Opera), the Schauspiel Frankfurt (Frankfurt Theatre), the Schauspielhaus Bochum (Bochum Theatre), the Puppentheater Magdebug (Magdeburg Puppet Theatre), the Theater der Jungen Welt Leipzig (Leipzig Theatre of the Young World). From time to time, you can also find the names of the architects in the names of the theatre, as is the case of the Semperoper in Dresden. Frequently the former use is hidden in the name of production companies, which are needed by theatre collectives of the independent scene for artistic processes, as in Kampnagel in Hamburg; or its current purpose as a place of reunion immediately stands out, as in Forum Freies Theater (Free Theatre Forum) in Düsseldorf (FFT).

Positions

We may be confused by the Theater am Gendarmenmarkt in Berlin. A classicistic building by the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, it was opened in 1821 as Royal Theatre, and was used as a Prussian state theatre between 1919 and 1945; today, however, it is a concert hall and can be rented for major events. Nevertheless there are still orchestras with their own concert halls, such as the Gewandhausorchester in Leipzig or the Berliner Philharmonie. As opposed to straight theatre, the infrastructure of music is widely ramified; even smaller cities have small orchestras, such as, for example, the Mitteldeutsche Kammerphilharmonie in Schönebeck an der Elbe. To simplify matters, they agreed on the label Theater- und Orchesterlandschaft (theatre and orchestra landscape), in other places its labelled municipal theatre system. The theatre and orchestra landscape as such was added to the state-wide directory of intangible cultural heritage in 2014 on the initiative of the Deutsche Bühnenverein and the Deutsche Musikrat (German Stage Union and the German Music Council).

Independent from the name-giving, theatres differ with respect to public funding, so-called subsidies. These benefits are either granted exclusively by the city, the municipality or the community, or are supplemented by state funds, or are exclusively supported by state funding, respectively. The contentions between theatre makers in the cultural field for a fair allocation of these funds have been going on for around 60 years. On the side of the artists, discussions are ostensibly held around the emancipative relevance of a specific aesthetic form; on the side of the politicians, the numbers regarding the occupancy rate are brought up for discussion; audience members themselves have diversified, which, in the sense of the concept of a theatre for everyone brought up in the 60s, means the inclusion of all societal groups. The latter development increasingly also comprehends stage operations as such, of which the post-migrant ensemble at the Gorki Theater or the RambaZamba theatre by people with intellectual disabilities are not the only examples.

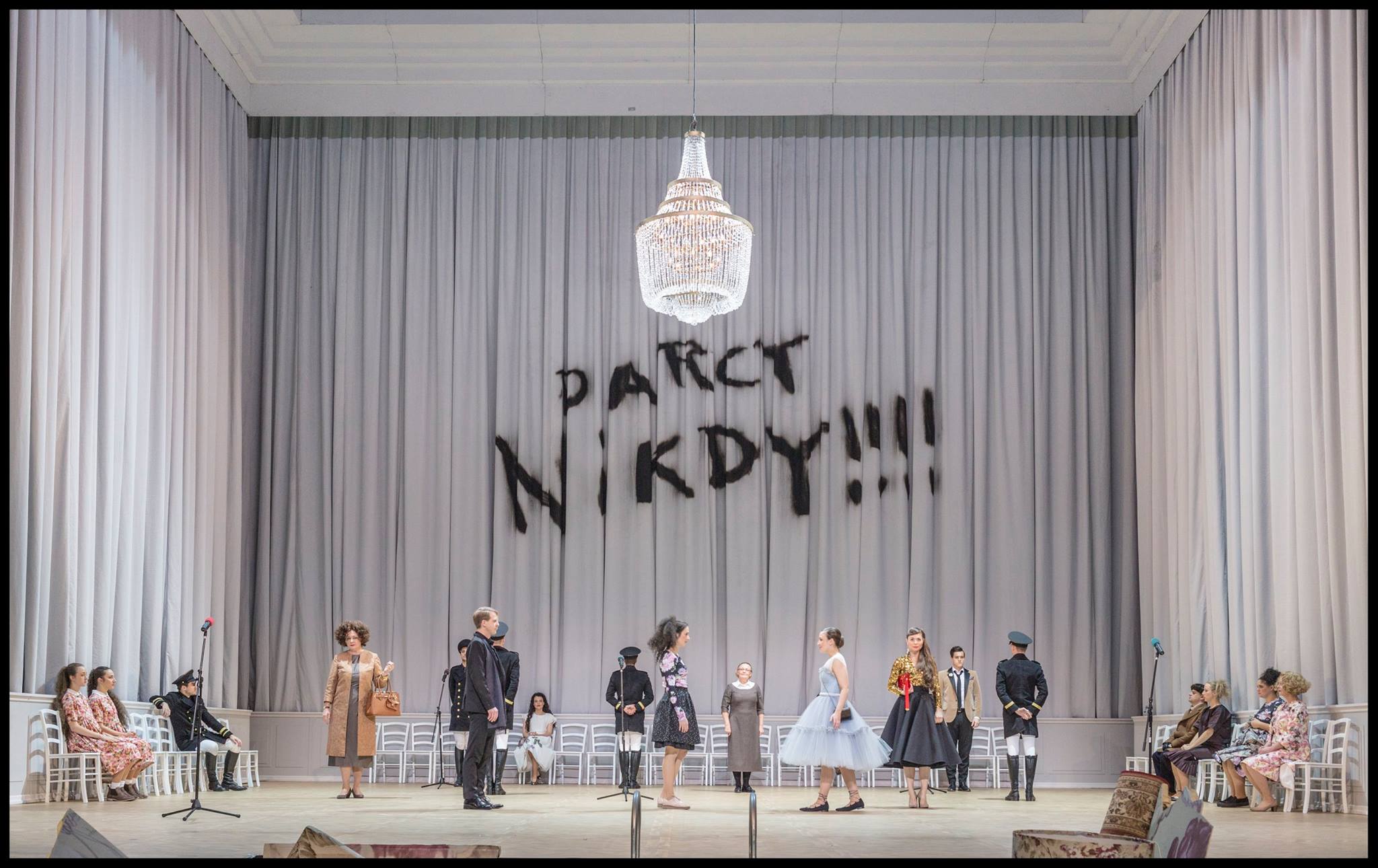

In the background, however, fiscal parameters create facts that force theatres into a transformation due to their structural establishment. The black zero is of central relevance in this context. This term is a metaphor for the debt brake that has been effective since 2009, and which dictates a constitutional limit to new debt for public budgets. In the so-called “new states”, where spending on the Reunification have increased the debt mountain, austerity plans have yielded specific consequences. We have furthermore observed that the legal form of a theatre has been changed, or that they are changing from cameralistics to double-entry bookkeeping, in the matter of accounting. Management companies like VG-Wort or GEMA are currently subject to a deep change as well. During this discussion about cultural diversity theatre makers insinuate that, in the name of cultural and creative industries, a connectivity to a global market governance is being created, which would cancel out means of production grounded in tradition. The current dispute about the Volksbühne in Berlin, during which a cultural secretary of state replaced the stage director and artistic director, Frank Castorf, with a Belgian curator and museum manager, is a textbook case for this discussion. Theatre makers speak of an enemy takeover and protest openly in order to protect their interest in the preservation of artistic freedom.

Basic Parameters

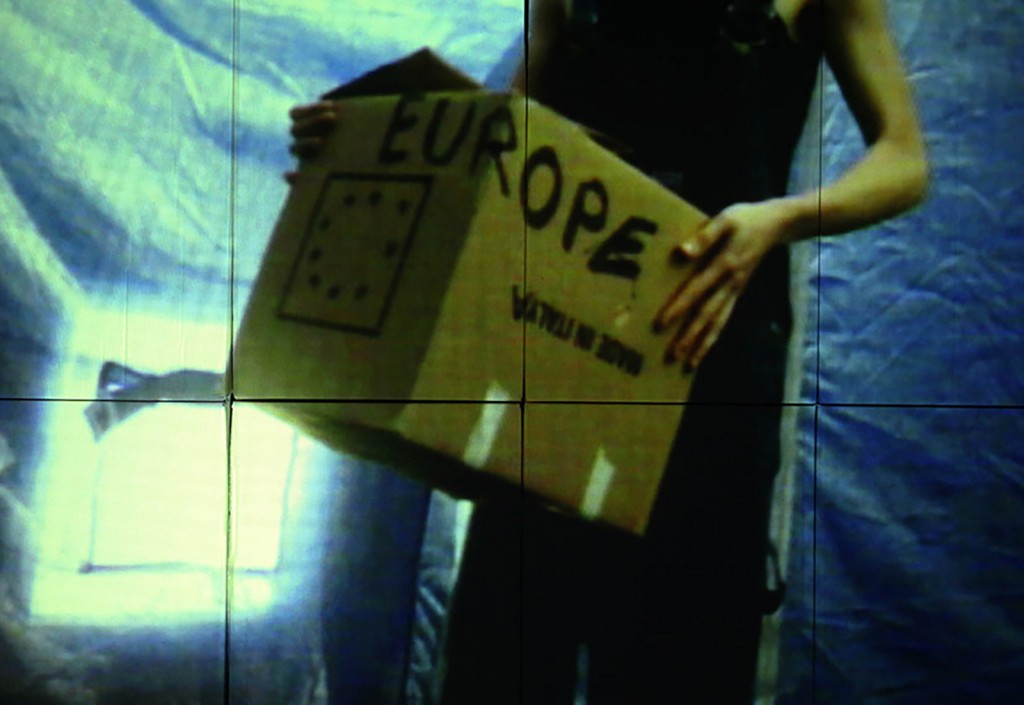

With the expansion of the EU domestic market in the 90s, which favours the Europe-wide call for open assignments, cities, communities and municipalities have begun competing with one another. This fact becomes clear with simple train rides. Signs and announcements in train stations treat cultural heritage often as a characteristic of the city: there is Bach-city, Luther-city, and many more. Theatre and orchestra are intensively included in the new marketing of a city. On the other hand, theatres have been closed, including the famous example of the Schillertheater in Berlin. After the reunification of the German Democratic Republic (DDR) with the Federal Republic, some 40 theatres were affected by closings in the so-called “new states”. A first understanding of the current make-up of the theatre and orchestra landscape requires a look into the responsibility for culture, both the financial basics and some central reference numbers.

a) Culture as a task for the states

The Federal Republic of Germany is a federal state in its borders from 3 October 1990, consisting of 16 states, whereby the city-states of Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg are considered states. The jurisdiction for culture comes from Article 30 of the German constitution. Legislation and administration fall under the domain of state culture. Since the federal government is not competent in this case, the term cultural sovereignty of the states is used. Likewise, the states are bound to the principle of subsidiarity. This means that the lower administrative units like cities, communities, or municipalities must give way when it comes to the resolution of state responsibilities and can only help in a complementary way. Performing arts belongs to a department of culture in a city, community, or municipality. There is a ministry of culture at the state level—as there was for example until the federal state elections in 2016 in Saxony-Anhalt—or culture is part of the ministry for family, children, youth, culture, and sport, like is the case for the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

b) Federal Cultural Politics

During the government of Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (1998 to 2005), the office of the Federal Commissioner for Cultural and Media Affairs (BKM) was created in the Federal Chancellery with the goal of bringing together cultural policy responsibilities that were previously carried out by different ministries. The current Federal Commissioner for Cultural and Media Affairs is Federal Minister of State, Monika Grütters. The federal government is directly involved in project advancement due to the founding in 2002 of the German Federal Cultural Foundation (Kulturstiftung des Bundes), which is located in Halle (Saale). The artistic director of this institution is Hortensia Völckers. One of the goals of this institution is the advancement of innovative programmes and projects in international contexts and to drive the cooperation with the Cultural Foundation of the German Federal States (Kulturstiftung der Länder). The general project funding and programme funding are directly responsible for project advancement in the area of performing arts. For project funding there is currently the program 360° – Fund for New City Cultures, with which institutions of all kinds are supported in order to diversify their programme, audience, or personnel and to promote the inclusion of immigrants and following generations. Furthermore, the programme TURN – Fund for artistic cooperation between Germany and African countries and the Doppelpass Fund, which supports the cooperation of independent groups and established dance and theatre houses. These existing cooperations can be expanded for a third partner, a theatre, or production house, even when they are located abroad.

c) The Financial Basics

For theatres there exist what are known as “theatre contracts”. They do not have the same weight as treaties, such as those with Christian churches and public broadcast (TV, radio). Churches can cite land they mortgaged to the government in the 19th century when they wish to secure an important source of income. The public broadcasting channels (with the exception of the Deutsche Welle) can rely on a broadcast fee treaty as well as a broadcasting financing treaty for the security of their financial needs. Since 2013, these treaties allow for the charge of 17,50 € each month per apartment, based on population and living space, which can hurt, even for independent theatre critics. The broadcasting companies were able to take 8.1 billion euros in 2015, with the help of various compulsory enforcements. This sum is almost equal to the total amount that was spent on art and culture in Germany, including monument conservation, national libraries in Leipzig and Frankfurt, performing arts and much more. In 2011, they took in around 9.4 billion, or 0.36 % of the gross domestic product. Theatres in Germany are unable to compete with churches and broadcasting companies when it comes to finances; although in terms of cultural policy, traditionally the theatre is also intended for sacral tasks in the sense of beauty, truth, and goodness, and thus has a certain spiritual responsibility. The artistic direction—also known as Intendanz in German—changes on average every four years, and the financial needs of the theatre must then be renegotiated, which the German Stage Union (Deutsche Bühnenverein) does on behalf of the theatre. Financial subsidies are pitted against an intangible cultural heritage whose production costs are covered by the administrative term public services. Theatres in Germany are equal to other public services like education, sanitation, hospitals, cemeteries, or interstates, hence the talk of “cultural care”, which, much like educational institutions, would govern the reach of theatres and orchestras based on a commuter belt and demographic statistics. In general, the financial contributions are voluntary services from the public authorities, which, unlike for churches and broadcasting companies, can be disposed of at any time.

d) Benchmarking Data

Indicators of a theatre are a permanent ensemble and a repertoire, which is why this is also called ensemble and repertoire theatre. The density of theatres and orchestras in Germany is characterized by 140 publicly funded theatres and 220 private theatres with 130 opera, symphony, and chamber orchestras, around 70 festivals, approx. 150 theatres and venues without permanent ensembles, and around 100 tour and guest performance stages, as well as many shows by independent groups. It is interesting to note that not one of these enterprises would survive without public funding. Yearly, 35 million spectators of all ages visit the approx. 126,000 theatre shows and 9,000 concerts. The German UNESCO commission in Bonn reported on this in its announcement from 19 December 2016, and made known that this theatre and orchestra landscape is nominated for the international UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage.

Associations

The Federal Republic of Germany is an area state in which unions are the central form of organization for groups that share a particular interest. The theatre and orchestra landscape is split into two large groups that are closely related to the post-war history of the Federal Republic of Germany in its borders before 3 October 1990. On the one side there are the so-called institutionalized forms of theatre work in the field of cultural policy, and on the other side are the so-called emancipated forms of theatre work. The original confrontation came about because of the student protests of the 60s, which dealt with the adoption of forms of aesthetic representation and its reformation. After an era of liberation of aesthetic limits between emancipation approaches and their subsequent institutionalization—that is, the broad integration of independent and in their own self-image emancipatory projects during the processes of metropolitan theatres in the 90s and the first decade of the new century—the conflicts of recent years have been postponed. This postponement is most noticeable in relation to the confrontation of the public sector with the debt limit, with the establishment of an EU domestic market, and the accompanying integration into city marketing, as well as with the novelty of the free trade agreements GATS, TISA, CETA in publications and thematic series. The social partnership that was established after the war is experiencing depreciation as a feature of the Rhine capitalism (Michel Albert) in the old states. Nevertheless, the two large groups define themselves based on their organizational structure to this day. On the one side there is the historic heritage, which precedes the social partnership: labour associations and unions. On the other side are the organizational forms of the independent scene.

a) Deutscher Bühnenverein (German Stage Union)

The largest interest group and at the same time employer’s association for theatres and orchestras in Germany is the Deutsche Bühnenverein, founded in 1846. It currently accounts for 214 theatres (34 national theatres, 84 municipal theatres, 24 state stages, and 72 private theatres) and 31 independent symphony orchestras (7 state orchestras, 23 municipal orchestras, 1 national orchestra) as well as 129 personally active members. Its responsibilities include: to discuss all artistic, organizational, and cultural policy questions, audience development, the formation of legal frameworks, and the social position of artists. Ulrich Khuon serves as president of the German Stage Union since 24 January 2017. Since 2017, Marc Grandmontagne is the managing director. Together they form the management. There are six groups within the union, which form the executive committee, represented by the chairman of each group: private theatre group (Christina Seeler, director of the Ohnsorg Theatre), directors group (Hasko Weber, general director of the German National Theatre & Staatskapelle Weimar), state theatre group (Hans Heinrich Bethge, senate director, Cultural Office of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg), state stage group (Kay Metzger, director of the State Theatre Detmold), metropolitan theatre group (Gabriel Engert, cultural advisor of the city of Ingolstadt), exceptional members (Charlotte Sieben, managing director of the Berliner Festspiele). The German Stage Union publishes theatre statistics, work statistics, books, brochures, and papers on cultural policy. It is a member of the Performing Arts Employers Associations League Europe (PEARLE*).

b) Genossenschaft Deutscher Bühnenangehöriger (The Guild of the German Stage)

A second large interest group is the Guild of the German Stage (Genossenschaft Deutscher Bühnenangehöriger, GDBA), which was founded in 1871 and whose current president is Jörg Löwer. This organization represents members of the artistic and artistic-technical sector. Organized into seven state unions, the GDBA covers the career fields of solo, dance, opera chorus, and equipment, technology, and management (ATuV). Specific types of contracts for workers rights in theatre can be traced back to them. Their members receive legal protection and consulting free of cost. Together with the German Stage Union, it upholds the stage court jurisdiction, meaning the trade court for the stage. An improvement in retirement arrangements is a goal. Responsibilities include pay scale policy and cultural policy, especially the definition of work and wage conditions for those associated with the stage. The GDBA publishes, among others, the German Stage Yearbook, the Journal of Set Designers (Fachblatt “bühnenbildgenossenschaft”), an updated copy of the normal contract (for the stage) and a commentary to the normal contract (for the stage). It is a member of the International Federation of Actors (FIA).

c) Further union representation

The Fachgruppe darstellende Kunst der Vereinten Dienstleistungsgewerkschaft (Occupational Group Performing Arts of the United Services Union) (Verdi) also offers union representation. Heinrich Bleicher-Nagelsmann is the unit manager. It offers legal advice and legal protection regarding work and social court lawsuits, civil service law, and job-related contract and copyright law, as well as consultation on employment references and test cases on work, social and administrative court in all courts, as well as strike support. Furthermore, there is the Vereinigung deutscher Opernchöre und Bühnentänzer e.V. (Union of German Opera Choirs and Stage Dancers) (VdO). It is both a professional association and union of the members of the opera choirs and dance groups of the German stages, Stefan Moser being the federal chairman.

d) Organizational Structure of the independent scene

Whoever is not employed by a theatre is considered to be independent. As far as social insurance coverage, this circumstance means that the Künstlersozialkasse (KSK) (Artists Social Security Benefits Office) is responsible instead of the Bayrische Versorgungskammer (Bavarian Provision Association). In addition to the Bund Deutscher Amateurtheater (Association of German Amateur Theatre), the so-called independent scene has an umbrella organization of all 16 state associations, mainly also due to the Bundesverband Freie Darstellende Künste (Federal Association of Independent Performing Arts), founded in 1990; it represents the interests of the approximately 2,000 independent theatres in Germany, amongst which solo theatres, troupes and theatre companies. Amongst other things, its responsibilities include consulting the cultural and social policy makers on matters regarding the independent performing arts, as well as effectively representing them. Members and interested parties receive information regarding tenders, performance locations, festivals, (advanced) education and technical questions via the regular information centre OFF-Informationen. The Federal Association considers the social and economic state of the dance and theatre creators one of the central themes. Janina Benduski (State Association Independent Performing Arts Berlin), Anne-Chathrin Lessel (State Association Independent Theatres Saxony), Tom Wolter (State Centre Acting & Theatre Saxony-Anhalt), Harald Redmer (State Office Independent Performing Arts North-Rhine Westphalia), Susanne Reifenrath (Umbrella Association Performing Arts Hamburg), Ulrike Seybold (State Assocaition Independent Theatres in Lower Saxony) and Axel Tangerding (Association Independent Performing Arts Bavaria) are its board members. The Federal Association Independent Performing Arts campaigns for a stable social security benefits office for artists and a good income for all of their colleagues. It fights for fair and transparent funding conditions. Another purpose is consulting public and private sponsors on the development and work of the scene. Last year, in cooperation with the Kulturpolitische Gesellschaft (Cultural Policy Society), Ulrike Blumenreich’s study “Aktuelle Förderstrukturen der freien Darstellenden Künste in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der Befragung von Kommunen und Ländern” (“Current Funding Structures of the Independent Performing Arts in Germany. Results of A Survey of Municipalities and States”) was published on this key subject. The first comprehensive study on the economic, social and labour-law related state of independent theatre makers in Germany was already published in 2010 in the “Report Performing Arts”, which the Federal Association Independent Performing Arts, together with the Fonds Darstellende Künste (Performing Arts Fund), got off the ground. The latter has been funding projects of all branches of performing arts since 1988. In the past 30 years, the fund has awarded approx. 16 million euros for approximately 3,000 individual projects and project conceptions in all federal states, and in more than 300 municipalities. The fund receives a yearly subsidy of currently 1.1 million euros by the federal commissioner for Culture and Media. Wolfgang Schneider (director of the Department of Cultural Policy at the University of Hildesheim), Ilka Schmalbauch (lawyer and advisor of the board of the German Stage Union) and Wolfang Kaup-Wellfonder (independent puppeteer) are its board members.

Lobbying, Representation, Networking

The Republic of Germany establishes a free and democratic basic order in its constitution, and this is demonstrated practically with the help of democratic principles. Due to the fact that interest groups organize in unions and that there is a pluralism in the landscape of political parties that allows each party a speaker for cultural policy, the Deutsche Kulturrat (German Cultural Council) is an umbrella union that represents all cultural associations and political contact persons for politics in matters of cultural policy since its founding in 1981. One of the main characteristics of the field of cultural policy is the caucus work, during which it works towards a balancing of interests and, when needed, a consensus decision. Furthermore, the media representation that builds an important basis for discussion and networking of theatre makers was and is a defining factor, leading to differentiation in the field of cultural policy, which in turn can bring about the creation of new forms of organizations.

a) Deutscher Kulturrat

The German Cultural Council serves as a contact in politics and administration in the states, at a national level and in the European Union. Its stated goal is to encourage discussions on cultural policy at all levels of politics and to defend the freedom of art, publications, and information. Central issues of the last years include the protection of cultural goods, copyright, free trade agreements, gender equality, cultural integration, economic and social questions or the issue of threatened cultural institutions by introducing a Red List. The managing board includes Christian Höppner (president), Regine Möbius (vice-president), and Andreas Kämpf (vice-president). The administration consists of Olaf Zimmermann (director) and Gabriele Schulz (deputy director). Members include the Deutscher Musikrat (German Music Council), the Rat für darstellende Kunst und Tanz (Council for Performing Arts and Dance), the Deutsche Literaturkonferenz (German Literature Conference), the Deutscher Kunstrat (German Art Council), the Rat für Baukultur und Denkmalkultur (Council for Building Culture and Monument Culture), the Deutscher Designtag (German Design Group), the Deutscher Medienrat für Film, Rundfunk und Audiovisuelle Medien (German Media Council for Film, Broadcasting and Audio-visual Media) as well as the Rat für Soziokultur und kulturelle Bildung (Council for Socio-culture and Cultural Education). Some of the associations mentioned are also members of the Council for Performing Arts and Dance and Ilka Schmalbauch is their contact person. The Deutsches Zentrum des Internationalen Theaterinstituts (German Centre of the International Theatre Institute) is also a member, and has made the mutual understanding of theatre cultures of the world its goal. Along with books, dossiers, addenda, and studies, the German Cultural Council publishes the journal “politik & kultur” quarterly. They also produce a free newsletter, with subscription via their website.

b) Representation in the Media

Beyond professional reports, local and cross-regional daily newspapers and magazines carry out reporting on theatre, in print as well as online. The Deutscher Bühnenverein publishes a monthly magazine, Die Deutsche Bühne. Theater der Zeit, theater heute, and nachtkritik.de occupy the space of theatre-specific publications. Along with magazines, Theater der Zeit also has a book publishing house which produces a yearly workbook dedicated to a certain artist or issue and includes academic essays (research series) or books on theatre architectures, copies of theatre pieces (dialogue series) or books about a certain theatre. The Alexander Verlag is one of the most important publishing houses among the theatre branches of the large publishing companies (Suhrkamp, Fischer, Hanser). Theatre publishers are important to theatrical distribution less for their image towards the outside and more for their internal representation, for example the Verlag der Autoren, Henschel Schauspiel Theaterverlag Berlin, Drei Masken Verlag, or Felix Bloch Erben. Last but not least is the Theateralmanach from Bernd Steets, which offers a short and manageable overview of updated questions on the topography of the German-speaking theatre landscape in the field of cultural policy.

c) Networking

Fusion and the closing of venues have characterized the changes to the German theatre and orchestra scene since 3 October 1990. Until 3 October 2003 alone, one in eight jobs at German theatre or operas were done away with, which equals five and a half thousand from forty-five thousand jobs. This broad fusion of theatres into theatre clusters in large swathes of land has led to a further loss of jobs and to the introduction of even more artists into the independent scene. This change in cultural policy has an effect on the labour agreements and finally on the net income and workload. Actors are worst protected from changes, a condition that has structural reasons. Even their interest representation is nowhere near as well positioned as that of musicians. Due to this dismantling of the German theatre and orchestra scene, actors have joined together against the poor labour conditions, against the low wages, and to fight for humane treatment. The newest example is the artbutfair initiative and the Ensemble-Netzwerk. Artbutfair works for fair labour conditions as well as appropriate wages in performing arts and music. The Ensemble-Netzwerk is a movement connecting theatre makers with one another and fighting for their labour conditions in metropolitan theatre and their artistic future. “Freiheit der Kunst, bedeutet nicht Knechtschaft der Künstler*innen” (“Freedom of art does not mean servitude for artists“) is the motto that inspires an overwhelmingly young generation to work together with unions, the Deutscher Bühnenverein, directors’ groups, politics, artists, and associated professional organizations. Their goal is to push for good occupational conditions for artists in public theatres.

Published on 6 June 2017 (Article originally written in German)