Václav Havel. A history of mentalities?

In their work on the revolutionary magazine of “microhistory” Annales, Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre outlined the principles of the Nouvelle Histoire movement, demanding that a historian collects the facts of the past society, trying to draw a “history of mentalities”. The current European set-up seems to challenge a cultural journalist in the very same way: after many discussions, the most successful approach in exploring the notion of “international theatre” is proved not to consider this as a static concept, but rather like a complex maze made out of fragments of different imageries.

We spent three days in Prague for a sort of “pilot edition” of the Crossroads Festival, created by stage director Michal Dočekal, director of the Czech National Theatre Drama and UTE President. As written in the booklet, the festival is dedicated to Václav Havel: “As an intellectual and politician, he strove to tell apart the fair from the foul and stood firm, espousing his knowledge of the fair.” Crossroads is a very sharp curatorial action: alongside a series of stagings of Havel’s plays, the first part of the festival invited theatre groups from countries which are dealing with severe political shiftings: Belarus (Belarus Free Theatre, Yuri Khaschevatsky), Ukraine (Dakhabrakha, Theatre for Displaced People or a debate with Nobel Prize laureate Svetlana Alexievich) and Russia (Teatro Di Capua, Viktor Shenderovich).

We attended some of the performances, but above all discussed the very aim of any networking programme in Europe, and how important it is to gather a group of people with different national backgrounds in order to, first of all, tackle different topics from different points of view.

When one tries to engage in a discussion on issues of global interest, it’s evident how often certain positions come from a perspective which is not always shared. This is because the history of a nation shapes the history of the thought of its people.

On the one hand, the very same topic can be addressed from a radically distant perspective from country to country—not all of them easy to understand for a foreign point of view—, on the other hand it’s evident how a vision of “international theatre” would be merely composed of a selection of few “samples” of national aesthetics and artistic trends, out of a much longer list of groups, artists and theatre companies.

This is in fact the basic strategy of the Conflict Zones Reviews editorial project: to keep its writers on the move both in metaphoric and actual terms, to let them visit foreign countries in search of those particular traces of a common thought around major topics. A key might be to look at them using comparative tools, each writer being aware of his/her own background and, at the same time, finding a way to put it to the test.

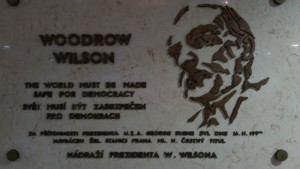

Amongst the most urgent questions in the nowadays shifting trans-national panorama is the one of national identity, a virtual umbrella which is very hard to keep on everyone’s head. The Crossroads Festival, hosted by the Czech National Theatre in Prague at the Nová Scéna playhouse, was held in the name of Václav Havel. It’s hard to detect at what point Havel’s devotion and talent for drama and his political career met, as hard as it is to define the nature of his status as an intellectual, his strong political activism and the extent of his power in the changing landscape of a Europe in the second half of the 20th century. The decision to dedicate the whole programme “to Havel, with love” is a statement by itself, it demonstrates the profound gratitude of the Czech people to their compatriot playwright and essayist, who had also been the ninth and last President of Czechoslovakia and the first of the Czech Republic, and who passed away in December 2011.

After a selection of eight plays (Havel authored a total of 22), the festival also presented Velvet Havel, a production by Divadlo Na zábradlí company, written by Miloš Orson Štědroň and directed by Jan Frič.

This performance can be used as a tool to shape out some considerations on the role of Havel in drawing a national identity.

Štědroň’s staging (Best Performance of the Year in 2013) is a vaudeville-like pastiche of humour and satire most likely serving as a very subtle tool to praise and, at the same time, to criticize such an extraordinarily charismatic and influential political figure. In absence of a coherent plot, the performance devises a crazy cabaret in which Havel—portrayed as a young man with rockabilly hair cut—is brought to life in a sort of purgatory, where he is asked to revise some of the key events of his private life in front of his uncle Miloš Havel, a very well known film producer.

Life is a cabaret!; In kino veritas!”. Dialogues, monologues, dance, songs and live music mingle up on stage creating a colourful variety show, really hard to follow for those who are not familiar with trivia about the former president’s life as a writer, lover and incurable smoker, always dividing his time between the responsibility of his political engagement and his artistic career .

It must indeed be remembered how unique the journey to independence from the Czechoslovakian communist regime was; that “Velvet Revolution” which also finds its echo in the title of the play. In only a month (November 17 to December 29, 1989), the former sovereign state of the Soviet bloc gave birth to a parliamentary republic, with absolutely no violent resistance opposed by the Communist Party, whose top leadership resigned after only one week of demonstrations and a general strike. Václav Havel, as one of the nine founder members of the text of civic initiative Charta77, played a key role in gathering the consensus around the independence from the Soviet Union, and a deeper attention to human rights. His service as President of the Czech Republic, although widely supported by the people, didn’t fail in receiving also some harsh criticism, especially with respect to certain foreign policy decisions.

Talking with some members of the audience after Velvet Havel, the impression is that such a humorous attitude in describing a popular figure and its influence on people is quite typical of the Czech. Jakub, a Slovak young professional based in Prague, tells a curious story: Největší Čech (The Greatest Czech) is the name of a television poll lunched in 2005 by the national broadcaster Česká televize through which the populace was asked to name the greatest Czech personality in history. The winner was Jára Cimrman, who couldn’t actually accept the prize; this anecdote perfectly captures the Czech sense of humour since Cimrman is actually a fictional character. Created by Jiří Šebánek, Ladislav Smoljak and Zdeněk Svěrák for the radio programme Nealkoholická vinárna U Pavouka in 1966 as a caricature of the Czech people, Cimrman ended up being recognized as one of the strongest Czech symbols, with books, plays and movies featuring him as main character or even as “putative author”.

Jakub’s opinion is that Czechs are not very politically involved and that the sense of humour shown in Velvet Havel is a trustful representation of a sort of national spirit, that—focusing more on the form than on the content—in Frič/Štědroň’s play finds a very subtle and respectful balance between criticism and apology.

In 2011 in Riga, the major Latvian director Alvis Hermanis presented Ziedonis and the Universe, a play which was both a homage and a critical response to the intellectual and political activity of Imants Ziedonis, the “national poet” who died not long after, universally recognized as the most representative icon of Latvian culture throughout the Soviet Union period and beyond. Here too, the play conveyed a mixture between revealing someone’s social influence and praising it. In both cases, the act of unveiling the contradictions of a society resulted in awakening a socio-political conscience. Facts and figures from the past (in the case of Czech Republic and Latvia: the Soviet political and economical influence, as well as the following cultural revolutions) appear to play a crucial role in terms of how people carve out the tools to tell their own collective history. As a matter of fact, such kind of satirical use of performing arts is strictly connected to the sense of community that reunites the conscience of the individuals.

Going back in 2016 Prague, a reflection that challenges this discourse can be found in the preface texts that introduced the Crossroads Festival booklet. The one by Michael Žantovský—director of the Václav Havel Library—summarizes Havel’s thought in a distinctive way: “Unlike all the other politicians, [Václav Havel’s] philosophy did not bear on an ideological doctrine and the necessity of power to apply it, but on the essential need of individuals to live an authentic, meaningful life, part of which is the awareness of being co-responsible for that which is around them and for the fates of other human beings.”

From this perspective, Havel wanted to engage the Czech people’s interest not so much through a strictly political propaganda able to foster an active intervention, but rather through conveying a sense of community based on a shared imagery able to make sense out of living as a collective of individuals. In other words: some ideas that proactively create an identity rather than an ideology that imposes one. This comparison with Havel may be accounted as good material for this little experiment of “microhistory”, which used performing arts to cast a light on the mentality of a country. And, once again, challenge a simplistic conception of “international theatre”.

Published on 21 October 2016 (Article originally written in Italian)