Europe Theatre Prize –

A Jungle of Languages

News

Established in 1986, after nine editions in Italy (in Taormina and Turin), the Europe Theatre Prize hit the international road and reached Thessaloniki, Wroclaw and St. Petersburg, involving a number of major institutions. The fifteenth edition was held in Craiova, Romania, between April 23rd and 26th, in connection with the tenth International Shakespeare Festival.

According to the press release, the Swedish choreographer and director Mats Ek was awarded with the XVI ETP for his ability “to mix dance and theatre in his own personal and very original expression”.

Since its third edition, alongside the main award, the Europe Theatre Prize Theatrical Realities “is aimed at encouraging trends and initiatives in European drama, considered in all its different forms,

articulations and expressions.” Winners of the XIII editions are Viktor Bodó (Hungary), Andreas Kriegenburg (Germany), Juan Mayorga (Spain), National Theatre of Scotland (Scotland/United Kingdom) and Joël Pommerat (France). A Special Prize was awarded to the Romanian master of stage directing, Silviu Purcărete, author of some astonishing rewritings of evergreen classics from Shakespeare to the Greek tragics.

The programme was opened by two performances of former winners, Thomas Ostermeier and Romeo Castellucci: Richard III and Julius Ceasar. Spare parts, as a liaison with the Shakespeare Festival. Then the National Theatre Marin Sorescu in Craiova hosted an intensive schedule of performances, round-tables, conferences and open discussions, a fruitful tool to get deeper into the artists’ world and, on the other hand, a precious platform for international networking.

A comment

The value of a prize can very much depend on the country where it is awarded. In those places where the arts struggle to get attention, facing a deep competition with other forms of expression and communication, a prize can function as a form of recognition, something that is able to create an outburst of emancipation and to strengthen the peculiarities of a language. Very often this function cannot manage to cross the borders of a very specific audience, which remains the same at the end of the day.

Nonetheless, the experience in Craiova showed that the value of the ETP lies in its inclusive nature: it’s a safeguarded environment in which artists and spectators have the chance to meet, discuss, and open their eyes and minds. The most important aspect of this three-day marathon was the opportunity of diving into so many different languages. The handcrafted dream-like work of Joël Pommerat, for example, proves to be attached to two strings: on the one hand, the quest for powerful and thought-provoking words , and on the other hand, the visual imagery of primordial cinematography. His company, Louis-Brouillard, funded in 1990, was able to draw a picture of contemporary society with all its contradictions through a form of theatre that, in his words, is “a possible place to interrogate the human experience.” Actors, music, and sounds are kept together by a subtle work on light designing, creating a continuous tension in the spectator’s attention.

Although similar in its urgencies (again dealing with contemporary issues), the Spanish playwright Juan Mayorga fills his plays with a stream of words that govern the frenzied relationships between characters of the everyday life. In Reikiavik—presented in Craiova—through a text that’s perhaps too long and wordy, Mayorga imagines the epic duel between two famous chess players (that reveals to be nothing more than a Pirandello-like “game of parts”) as a metaphor for a lifetime battle in which everyone struggles with a destiny that appears to be already written in a book.

Viktor Bodó‘s collective actions (his Sputnyik Shipping Company toure d Europe extensively) represent a very complex, articulated and multi-layered scenic text in which contrasting styles coexist in the same time/space span. Absurd theatre, pantomime, and visual theatre meet with biting irony.

Throughout his intensive work on major German stages and international collaborations, Andreas Kriegenburg has established a signature tone. The most evident characteristic is an amazing visual impact and insight into some cornerstones of Occidental theatrical literature. The German director’s three-hour staging of Lessing’s Nathan the Wise has been quite an experience for the foreign audience, challenged in following the surtitles, and at the same time amazed by such strong mastery of acting and stage movement.

The National Theatre of Scotland, a rather young institution, has proved to be open to tough challenges in producing new plays and pursuing high quality standards. And it’s laudable that an international prize was able to widen its perspective beyond the career of a single artist and towards the definition of a line of work. Last Dream (on Earth) (created and directed by Kai Fischer, presented in Craiova) is a storytelling piece that intertwines the desperate journey of an African refugee to Spain with Gagarin’s attempt to the Moon landing. It’s a sort of radio drama listened through earphones, and nonetheless completed by the sight of the actors/musicians on stage, immobile on their stools, yet kept alive by a very thin path of small movements and gestures.

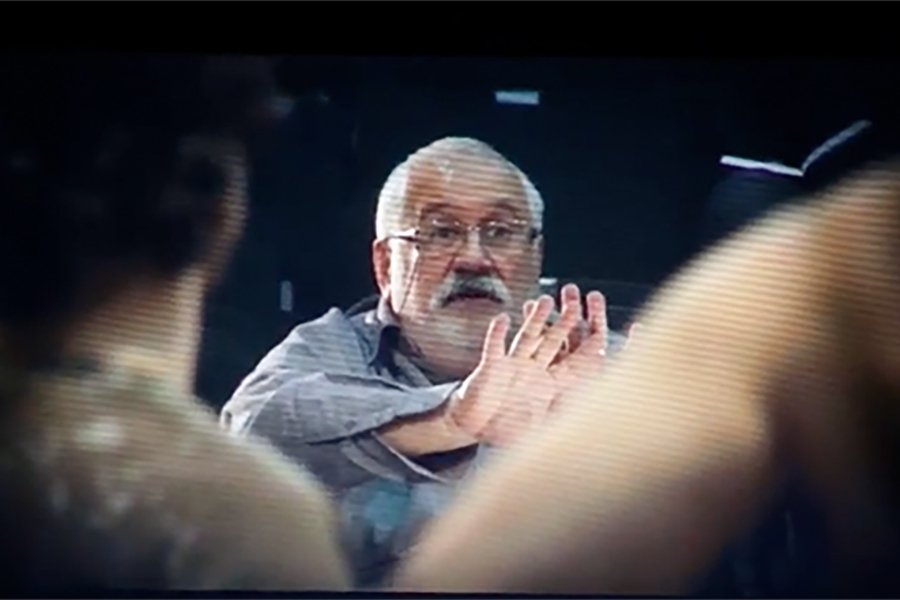

If, at first sight, the choice to replace a live guest performance with a video projection appears disappointing, the audience was eventually rewarded by being given the opportunity of entering Silviu Purcărete’s mind through the documentary Within A Tempest. The Island (by Laurenţiu Damian). Watching the great Romanian artist directing his actors through Shakespeare’s final play gave back the essence of creative work, with whirling ideas flowing in and out the stage, building up and crumbling down whole portions of intuitions.

Curated by the Swedish critic Margareta Sörenson, the meeting with Mats Ek (more than any other) helped the audience to embark on a trip to this master’s imagery, featuring comments and notes by a group of scholars and critics. Ek’s attention to female characters was only one of the focuses that put this choreographer in the centre of a committed research on the essence of the human being: as Ada D’Adamo stated, “even when detached by a narrative dimension, dance always leans on expression, because it is driven by a human body. It never limits itself to being a frozen hieroglyphic, it’s pure passion in flesh and bones.” Ek rewrote some classic 19th century ballets, marking a new path which is nonetheless in debt to some other artists’ lesson, and yet incredibly personal. Pieces, such as Giselle (1982), The Swan Lake (1987), Carmen (1992) and Sleeping Beauty (1996) are characterized by a sharp care for costumes and gestures, and very simple in the visual approach, often featuring only small objects or pieces of furniture. “I’m in love with bodies”, Mats Ek said at the meeting, “with real bodies, sometimes ungraceful, sometimes unpleasant; but a movement must be authentic, and therefore beautiful.”

The piece Axe, choreographed by Ek, featuring Ana Laguna and Yvan Auzely, was a very gentle and elegant grand finale of the awards ceremony: the simple action of woodcutting (with real wood and a real hatchet) grows more and more rhythmical; Laguna is like a ghost of late past crossing the space and passing through Auzely’s memory, resolving in a heart-breaking last dance.

That’s how a thick dramaturgical texture and a perfect technique establish a strong connection between those real bodies and their complex psychological and emotional substratum: in Ek’s words, “It’s impossible to separate body and head. The point is not how the bodies look, but the interaction between body and actions.” Due to austerity measures, this year the Prize (originally 60.000 Euro and 30.000 for the ETP Theatrical Realities) was drastically reduced; to the point where we might question the sense of such an operation, when more money might be better invested in finding new opportunities for promotion and touring.

The ceremony itself, broadcasted by the national TV station, and attended by a considerable number of young and non-habitué spectators, was somehow too formal, and at risk to crystallize the image of the current theatrical vitality. On the other hand, the glimpse we get into such a high number of different theatrical languages allows us to compile an executive summary of the artistic reflection on contemporary issues. The conferences, open discussions, and even the informal moments of small talk in the beautiful hall of the Theatre Marin Sorescu might be the highest achievement in drawing a picture of the actual urgency of contemporary European theatre: to get together, to talk, to discuss, to fight.

Rather than recognition, assertion, and agreement, we might need doubt, dissent, and productive disagreement to prove that the cultural level of the multi-national discourse is the foundation on which any other form of “community” should be built.

As in any well-written play, a strong dialogue is made through contrasts. Treasuring these opportunities of encounter, the cultural community might use arts as an ethical barometer; fostering the ability to show the differences, and sometimes to preserve them, might be the way to pose a question: to which point can and must we consider ourselves to be similar in order to be part of a group of free minds?

On this premise, a common dock for mooring ships carrying loads of doubts is the most precious prize we can award each other.

Published on 24 May 2016 (Article originally written in Italian)