Talking theatre and changing socio-political landscapes with Gorčin Stojanović

Sundays are meant to be calm and relaxing. Yet, the third Sunday of September wasn’t that at all in the capital of Serbia, Belgrade. Instead it was a day, charged with anxiety, hope, fear, politics, and visions for the future. The day concluded with the FIBA’s EuroBasket 2017 finals, where the Serbian national team lost to the Slovenians; and everyone was watching, including everyone in the theatre. At the same time, since the early morning, the city centre had been preparing for the Pride Parade, which later made it to the headlines as the first event of its kind in the region, led by Serbia’s prime minister. Last but not least, the second part of the UTE’s Conference on Theatre Structures took place at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre (A/N Jugoslovensko dramsko pozorište in Serbian, wildly known as JDP).

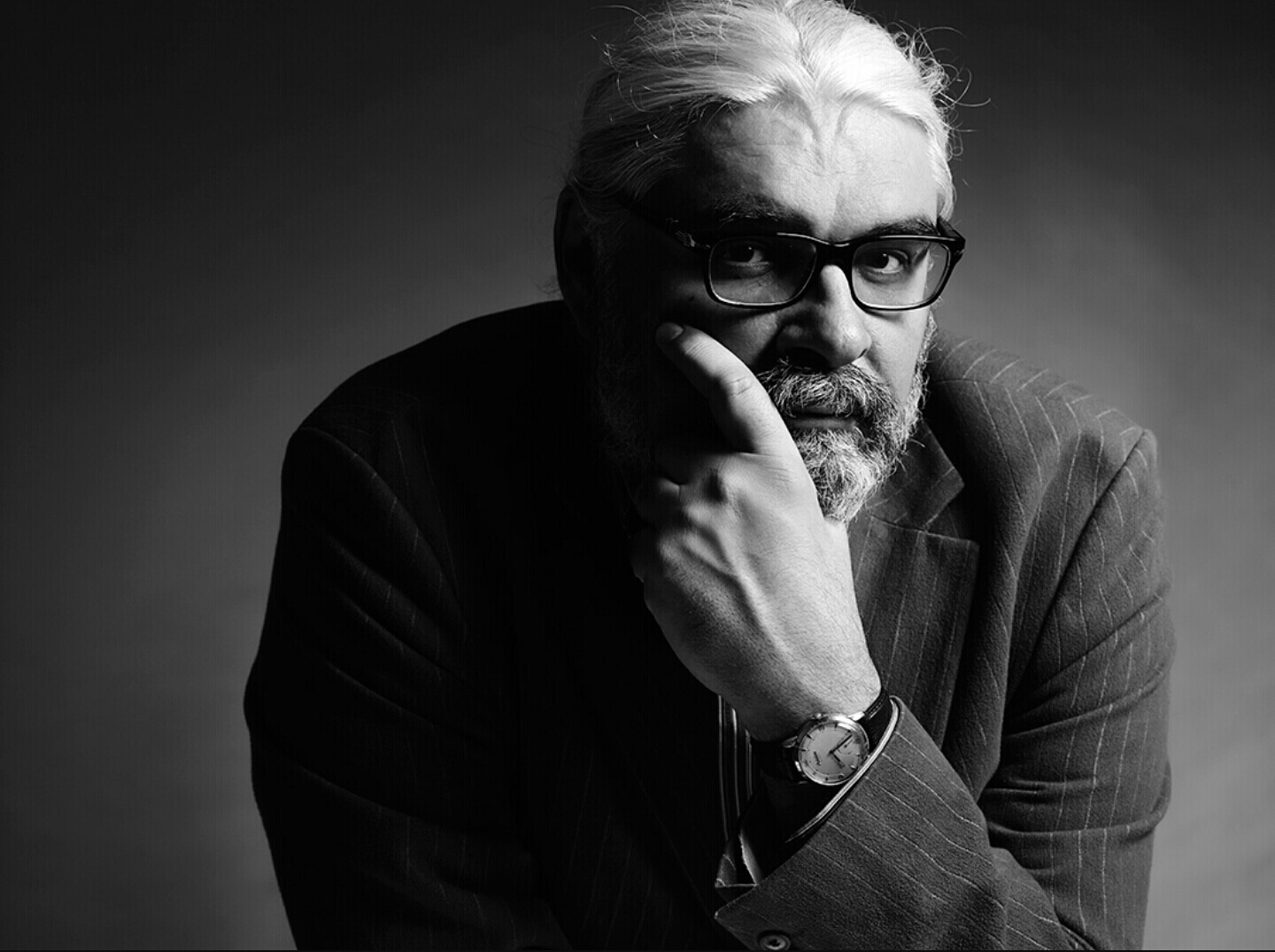

In the middle of this busy Sunday, when the thickness of the boundaries between politics, society and theatre happened to be so tangible in the context of this city, I talked to Gorčin Stojanović, since 2001 the artistic director of our kind host theatre. And since it seemed to me that his position required a great ability to link what happens on the stage, inside the theatre, to what is going on outside of the building, on the street or into the stage of politics, without letting it harm the artistic autonomy and esthetics, he felt like the best person to speak to this day.

Let’s start with the most obvious questions: Yugoslavia as a political entity is gone but the Yugoslav Drama Theatre is still standing and its name as it was declared by Josip Broz Tito in 1947, when it was established, remains unchanged. How come and what is the message behind that?

Gorčin Stojanović: It’s very simple: this theatre is too much of a brand to be easily renamed. I don’t like using the word “brand”, and I am not doing in ironically, but I need to in order to explain this. And I am talking as a businessman on purpose. It’s just that you don’t rename good products. There are two big brands in the field—the Yugoslav Drama Theatre and the Yugoslav Cinematique, the third cinema factory in Europe and the fourth in the world in terms of funds. And it’s also still called Yugoslav Cinematique because if you changed the name you’d have to start all over again, and you’d delete a 70 year-old tradition.

In the case of JDP, there was some public discussion regarding its name, though not all too much and there hasn’t been any strong pressure to change it. But it’s probably interesting to note that those comments into that direction were not coming from the far-right but from the moderate nationalists instead. And when nationalists ask this question, I always answer one and the same thing: you know that in Berlin there is a Maxim Gorki Theatre. Probably they could have called it Leo Tolstoy or Fyodor Dostoyevsky but they didn’t and named it after Maxim Gorki because he represented an ideology as well. And after the Berlin Wall came down no one thought of changing its name. Because it is a brand and very famous. You don’t rename it simply because the state has changed. So the Yugoslav Drama Theatre will not be renamed either, at least not during our time.

What you just said also exemplifies the complex relations between nations, as imagined communities, culture, political representation and various structures. That naturally leads to the next question, which might be slightly politically incorrect. But, omitting crucial contextual factors and focusing on structures only, you have this experience of living in a transnational union like Yugoslavia, where different nations coexisted. Today we have the European Union, which in a very broad sense also tries to create a larger, overarching structure, covering many different nations, though the process of becoming part of it is completely different. Given your experience, what are the lessons learnt—for good or bad—which should not or should be repeated?

Gorčin Stojanović: Absolutely! And the politically incorrect questions are my favorite ones. Four years ago we held a small conference at the JDP, at the same place where we are today, particularly on this question. Its intention was precisely this: to explore the question of this multinational, multicultural, multi-whatever bodies. And the main thesis was very simple: the Austro-Hungarian Empire was demolished due to nationalism—and here I am talking only about the structures, not about political systems. The Austro-Hungarian state, as we know, was reaching out to some parts of our world, and some of the roads and the railroads that we still use were built back then. The modern infrastructure came with them. Afterwards came the first Yugoslavia (n.b. Kingdom of Yugoslavia) and then the second Yugoslavia (n.b. Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia). And it developed everything further. The building that we are sitting in at the moment was erected during this period. So, in terms of structure, Yugoslavia bears resemblance to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And it also collapsed. So what makes us believe that European Union will stand forever?

That is why in 2013 I brought three people together—Dubravka Stojanović, a great historian specialized in the Serbian history after the Vienna Congress in 1878 till the First World War, who is leftist in her political views; Predrag Marković, another great historian, who is more right in his political views, you might even say a mild nationalist, but a great scientist and would not make any compromises with the facts; and Milica Delević, an economist and European Union expert. And on the grounds of what had happened before from a historical perspective and what was the situation at the moment, they were able to predict a lot of what happened later: the rejection of the EU Constitution in The Netherlands and France, also Brexit. All of the things that people knew of and preferred to ignore.

Even some early origins of the Conflict Zones project were envisioned in this conference. The UTE president during this time, Ilan Ronen, even suggested that Belgrade should be the headquarter of this project, but the Serbian Ministry of Culture did not realize its potential. And this is the long story, trying to say that of course there is always something good and bad in these structures. But what the Yugoslav Drama Theatre still stands for in the region is that we do collaborate and have always collaborated with each other. We may not have invited that many Croatian directors during the war, for instance, but still the JDP was the first theatre which went to Croatia and Bosnia without any mediation.

As a matter of fact, that was the second part of my question that you already started answering—what is the role and place of arts and theatre in particular in these structures, and how are they implemented through representative institutions such as the Yugoslav Drama Theatre?

Gorčin Stojanović: In 1995, the JDP had this production “Powder Keg”, a play by Dejan Dukovski from Macedonia, directed by Slobodan Unkovski, which was invited all over the world, from Colombia to Rome. But the most important thing is that the first time something ever went from Serbia to former Yugoslavia, to Croatia and Slovenia, it was “Powder Keg”. And the first time a major theatre went to a festival in Sarajevo, again without any mediators, it was again the Yugoslav Drama Theatre with “Powder Keg”. Later, Slovenians came with seven productions to two theatres in Serbia. We were joking that this was a Slovenian invasion. And one of their main actors told us, “Well, we had to come to Belgrade, as Belgrade is the main city”.

What is more, I have calculated that in the past 15 years, the JDP has gone to Zagreb more frequently, and Croatian theatres have come to Belgrade significantly more than before, when we were, so to say, one. And that tells you something. Everyone needs their state and that’s politics. But culturally we are so much connected and that is something different.

And when you prepare the artistic programme of the Yugoslav Drama Theatre today, who are the envisioned audiences? Or, if we go back to business language, who are the target audiences?

Gorčin Stojanović: I can give you a very precise answer. Our audience members come here not only because of the sensuality of theatre but also for its intellectual dimension. I strongly believe that whatever JDP does it has to unite those two dimensions. In different proportions, but both have to be present. Sometimes I really like to laugh and to direct bedroom farces which do not keep me alert that much. However, the audience at the JDP comes for something more. If we try to do something stupidly commercial, they would not be interested. And our directors, actors, set designers… everything is too good for that. Which means that we cannot do cheesy theatre even if we want to.

And this is because the tradition of the Yugoslav Drama has always been a combination of several things. First of all, a high-level of performance skills, meaning the best actors. JDP was based on the model of The Moscow Art Theatre and conceived by taking the best actors from all over Yugoslavia. That was the model but it changed rather quickly. The first premiere of the JDP was on April 3rd and by the end of June we broke up any relations with the Russians. So the model was not maintained from here on in, but the elite of actors and this idea stayed. Secondly, it has always been a director’s theatre with strong directorial figures, doing daring work. Some of our most daring and politically engaged productions, like “Powder Keg”, lasted on stage for more than 10 years.

In 1969 the only official ban of theatrical performance happened. It was a performance on the dramatization of Drajoslav Mihailovij’s book “When the Pumpkins Blossomed”—one of the best Serbian novels turned into a very artistically and not politically daring piece of theatre at that time. It included one sentence—the kid is addressing the Communists, who came in 1948 to arrest his father and says, “You are worse than Germans” and adds something like, “Russia sucks”. And Tito, who never saw the production, referred to it in a speech and it was banned. And from this moment on something was broken for the next four or even ten years inside the theatre. Not artistically but internally.

In 1985, Jovan Chirilov, a very prominent figure in our theatre history, was elected by the younger members of the troupe and became part of the second management of the JDP. And he was part of the theatre before, thus always working for the Belgrade International Theatre Festival (BITEF), so he was quite knowledgeable. And what he did was to formulate four pillars, that were already there, but he stated them clearly and made them part of the official structure of the repertoire: foreign classics, domestic classics, foreign contemporary plays and domestic contemporary plays. Yet, the requirement was that the classics should always be done in a daring way. It should be a new reading of a classical piece for theatre. Thus, he insisted on bringing in young people—I was one of them. And I did my first production when I was in my 3rd year of the Theatre Academy.

So now you are paying it forward?

Gorčin Stojanović: Yes, exactly. My only mission for the past 17 years that I have been around the JDP artistically has been to do that: to enable young people to develop. And the idea of excellence is always there. No doubt that you cannot always reach it but you definitely need to strive for it. Even more so in time of crisis! In good times, when you can have seven or eight openings per season, you can probably sacrifice one or two of them. Of course, even then you still do your best, though it might not turn out to be the best. You just cannot limit yourself to trying to fulfill someone’s very specific need but you have to try to do your best. Every compromise is good except for the main compromise of doing something without an artistic reason. The artistic reason could also be wrong sometimes. For instance, I may not agree with everything we have produced artistically, yet I still stand behind everything, even the greatest fails. Luckily, due to this very precise planning, we haven’t had many of them. So my idea is very simple: I am trying to pay forward the chance that I was given as a young director by Jovan Chirilov. This means that directors now come to my office and we talk and talk and exchange thoughts, ideas, and plays. Because, like in soccer, if you do not do well in this team you will end up in some other, group “B” club, which is not Manchester United. So I try to keep that from happening, young people being sacrificed that way. Because this is what we had with Jovan Chirilov—this care and concern, pushing us to make good productions and not to have time to sleep.

And what is next? What should we be looking forward to seeing on the stage of the JDP in the upcoming seasons? And what are future directions that you are envisioning?

Gorčin Stojanović: Right now, we are working with Slobodan Unkovski, a very well-known director in this part of the world—from Athens to Ljubljana. He is working on, what I call a fifth column in our repertoire that appears from time to time, the experimental stuff. The production is called “Einstein’s Dreams” and is based on Alan Lightman’s book, which is not necessarily a piece of fiction, as the author himself is a scientist.

The second upcoming production is “The Mercy Seat” by Neil LaBute, staged at the Studio JDP by the young director Jana Maricic.

Then we will have a new premiere by Iva Miloshevic, who is staging Ivan Turgenev’s “A Month in the Country” with the very renowned Mirjana Karanovic. Then we will do a play by Ivan Cankar, a Slovenian classic, “The King of Betajnova”, which actually was the first performance done at the JDP in 1948. And I think this is a nice illustration of what I have said earlier because this production will be staged by a young, promising director whom I invited to talk to. After a while he told me that he wanted to stage this play. I asked him whether it was because of the anniversary, but he did not know about it and got embarrassed. And I told him, “Even if you lie, I don’t mind because the play is a great choice, and the JDP is the place to do that.”

And the dream is always the same: to have and keep what I called our three “Es”: exclusivity, excellence and esthetics.

Published on 26 September 2017 (Article originally written in Bulgarian)